Recognizing patterns is something we do all the time, looking at a work of art or a building, the landscape we’re driving by (perhaps too much in a hurry to really appreciate the details) or perhaps even patterns of behavior in friends and co-workers.

The repetition of patterns is something we might sense rather than realize: the rhyming or rhythmic patterns of poetry or lines from Shakespeare, for instance.

In art, patterns may exist in the placement of objects in a realistic setting that may “comfort” us because they’re familiar or, in an abstract sense, amaze us in the way patterns are used to fill space: I’m thinking particularly of MC Escher and his tessellations.

In music, hearing “interval patterns or shapes” in a melody may help us trace that melody as it evolves or develops. Becoming aware of these helps us through a musical style that may not be readily familiar, if you miss the recognizable “musical landscape patterns” we associate with more traditional melodies, harmonies or forms. This is why I often talk about “gestures” and recognizing them as they recur rather than melodies, approaching a piece on its own terms rather than a previous century’s.

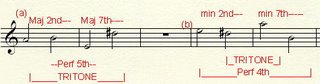

The Symphony I’d finished earlier this year grows out of a single four-note cell – see (a) – which consists of a rising major 2nd followed by a rising major 7th. Internally, there’s another pair of intervals, a perfect 5th and a tritone. By switching minor for major and reversing the pitches, there’s another shape that basically inverts the direction of the intervals – see (b).

I could also describe it as “a narrow interval followed by a wider interval” which might allow me to use a minor 3rd and a major 6th and so on to get a slightly different set of pitches, and by doing various things with directions and expansions create a fair bit of variety while sticking to a basically recognizable pattern. The pattern can become integrated into the texture as part of the line or the harmony until it’s almost subliminal, but it creates a consistency and cohesion to the music as it unfolds.

I could also describe it as “a narrow interval followed by a wider interval” which might allow me to use a minor 3rd and a major 6th and so on to get a slightly different set of pitches, and by doing various things with directions and expansions create a fair bit of variety while sticking to a basically recognizable pattern. The pattern can become integrated into the texture as part of the line or the harmony until it’s almost subliminal, but it creates a consistency and cohesion to the music as it unfolds.So I’m working on the next phrase of this rock-motive for the violin-and-piano piece which, as part of an inside joke, uses Shostakovich’s musical signature – DSCH – as a tag.

I was noodling at the piano – improvising on what I hoped might work – and came up with this:

That sounded cool, but I wasn’t sure if it “worked.” Then I started looking more closely at the pitches.

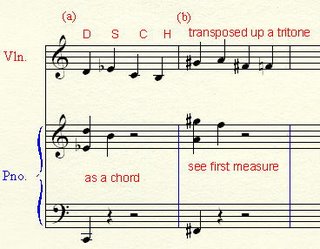

If I take the Shostakovich Signature and turn it into a chord, I get (a). If I transpose it up a tritone (my equivalent of tonic to dominant), I get (b).

Now, look at the pitches in the previous example... which I came up with purely spontaneously but which incorporates the DSCH-motive into the harmony. This became the opening of the next pattern – adding a violin “wail” to the rhythmic pattern turned rock-motive:

(Software disclaimer: since Finale NotePad doesn’t permit me to use meters like 7/8, I am stuck writing it out in 4/4 without the easier-to-read-and-play changing meters of 7/8 and 4/4...)

(Software disclaimer: since Finale NotePad doesn’t permit me to use meters like 7/8, I am stuck writing it out in 4/4 without the easier-to-read-and-play changing meters of 7/8 and 4/4...)In the original motive, the violin played the 16th-note DSCH tag, but now that it was playing this counter-line, there wasn’t room for the tag, so I switched it to the piano part in measure 2. If you take the DSCH motive (a) – two minor 2nds a minor 3rd apart – turn them into Major 7ths (b) and then expand them in an outward direction, you get a shape – (c) – that is still a recognizable pattern because of its rhythm and its placement in the phrase but is also, more subtly, based on the same interval pattern.

In a neat analytical turn, all these pitches create hexachords that are the closest related sets to the primary set I’ve been using in the Theme & Variations and, so far, in the Scherzo. Which is good because otherwise, theoretically speaking, I would have to go back to the drawing board to find something that still sounds good but also works technically (like somebody’s going to say, “You know, Dr. Dick, there’s no relationship between the notes of the second chord and the notes of the first chord... minus 5 for you” - on the other hand, rules are made to be broken but first I like to make sure the rules don't come up with something better).

In a neat analytical turn, all these pitches create hexachords that are the closest related sets to the primary set I’ve been using in the Theme & Variations and, so far, in the Scherzo. Which is good because otherwise, theoretically speaking, I would have to go back to the drawing board to find something that still sounds good but also works technically (like somebody’s going to say, “You know, Dr. Dick, there’s no relationship between the notes of the second chord and the notes of the first chord... minus 5 for you” - on the other hand, rules are made to be broken but first I like to make sure the rules don't come up with something better).Anyway, recuperating from what has now turned into a cold (though not bad enough your computer is in any danger of catching a virus from me), it is time to get back to the piano.

No comments:

Post a Comment