"There was some criticism of blasphemy in the texts, to which Schoenberg responded, 'If they were musical, not a single one would give a damn about the words. Instead, they would go away whistling the tunes'."

*** ***** ******** ***** ***

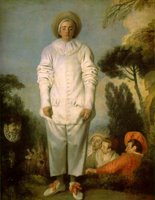

According to many books about 20th Century music, there were two (or three) significant works that heralded the start of “something new” in the direction music had been taking since the 1890s. One was Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and the other, perhaps more famous (certainly more frequently performed), was Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring. Writers often mention Claude Debussy’s Jeux (“Games”), also a ballet, which was premiered May 15th, 1913. Stravinsky’s ballet would be involved in one of the great riots in music history at its premiere in Paris, two weeks later – on May 29th, 1913.

|

| page 1 of Pierrot Lunaire |

Aside from the fact it seems odd to imply “the 20th Century began during the 1912-1913 Season,” it’s also strange that a work that’s now 100 years old is one that is still the subject of controversy – if not for itself, then for what it led to.

I would prefer to think of the Centennial Anniversary of Pierrot as being July 9th, 1912, when he completed the work, but such dates are important only to other composers, I think, since most writers tend to believe less in the roles of creative inception or even its delivery as in the “second delivery,” when the work is first presented before the public – either as a performance or as a publication.

This can lead to confusion, in some cases: Beethoven composed his Op. 95 String Quartet, the Serioso, in 1810 but didn’t publish it until 1816 which may seem no big deal to the average listener or concert-goer, but once you start thinking about what was going on in his head at the time he wrote it – or even what was going on in his life then, the date it was published is misleading.

Of course, Schoenberg himself can be an example of this: anyone familiar with his luxurious Gurrelieder, a huge oratorio-like choral work, wasn’t premiered until 1913. To see that date and then see Pierrot Lunaire on a list of works dated 1912, it makes no sense, stylistically. Even though he “finished” the work in 1910, it’s still difficult to follow the differences in style.

Actually, he’d begun working on Gurrelieder in 1900 originally as a song cycle for soprano, tenor and piano for a competition but missed the deadline by a week and so decided to “expand” it considerably. After essentially finishing it in 1903, he realized the orchestration was proving to be so time-consuming (and with no prospect of a performance in sight) he put it aside, completing it in 1910 then still waiting three years for its premiere. The first two parts were written under the clear influence of Wagner – evident in Schoenberg’s most frequently performed and, by later standards, accessible piece, Verklärte Nacht (“Transfigured Night”), written in 1899. By the time he’d written the final part of Gurrelieder, he had come under the influence of Mahler whom he'd met in 1903 (Mahler had finished his 5th and was starting work on his 6th Symphony).

Since (roughly) around 1600, a musical work started in one key and ending in the same key (or – always an exception – from the minor mode to the major mode; or, less often, if the major mode is impractical, like B Minor to B Major (with 5 sharps and very difficult, then, to play in tune), you could always slip into the relative major, D Major (with 2 sharps and a brilliant key for trumpets, especially), like Bach did for his B Minor Mass).

But ever since Wagner wrote Tristan und Isolde (completed in 1859, premiered in 1865), the traditional concept of musical organization we call “tonality” began to come undone. The harmonic direction – how the chords in one key moved to reinforce this gravity on the “local” level – became so chromatic, modulating so freely, it was hard to tell what the tonality really was, just listening to it (in one very dramatic moment of Mozart’s G Minor Symphony, K.550 (1788), the chords change, modulating so quickly, modern-day writers often point to it as the birth of “atonality,” something we blamed Schoenberg for 125 years later). Even Wagner pulled back from his rampant chromaticism in Tristan because how much further could you go? Franz Liszt wrote short piano pieces often titled something like “Bagatelle without Tonality” in the 1880s.

Mahler often used a “progressive tonality” which, though less chromatic, focused less on the final resolution of the tonal implications of a work’s traditional structure. Mahler, to us today, would never sound non-tonal, but because he might begin in G and end in E Major (his 4th Symphony), he was already working at weakening the gravitational pull of three centuries of music theory.

While Schoenberg “inherited” the chromatic style from Wagner and, later, Mahler, he is credited with the “invention” of atonality, the dissolution of the tonal “pull” of one chord to move logically to another chord, establishing a hierarchy of motion which can be heard on the local level (the phrase) or on the larger (macro-) level (the work). Despite his unsettling and often free-wheeling use of chromatic tonality in his 1st String Quartet (1905) it wasn’t until his 2nd Quartet (1908) that he wrote what is recognized as his first “atonal” music, the final movement which, in addition to the quartet, adds a soprano to sing the poem beginning “I feel air from a different planet.”

After this came several pieces, some small-scale, some large, in which he explored this new way of organizing sound – in what, actually, does not sound organized. For all its rules, classical music’s Tonality is a system in which everything is organized around a central focusing pitch – the tonality – and when you take this away, this center, gravity collapses and you have, as most people would react, “chaos,” compared to the music they’ve been listening to for centuries.

And so, Schoenberg earned his reputation as a “destroyer.”

In a previous post, I quoted a passage from another work he “composed” at this time, his theory book called Harmonielehre or “Harmony Textbook” (more euphoniously translated as “Theory of Harmony”). There are always generational differences between the Old(-fashioned) and the New(-fangled) and it’s typically perceived New Ideas are out to destroy or replace the Accepted Ideas of the Present Day (without realizing they were probably once the New(-fangled) Ideas of the Past).

After describing new ideas as an aspect of growth, like the natural flowering of a tree, Schoenberg concludes: “Short memory and meager insight suffice to confuse growth with overthrow."

Curiously, Schoenberg writes in an essay humorously entitled “How One Becomes Lonely” (1937) that the publication of Harmonielehre gave him a kind of respect among musicians – he was writing about traditional concepts of harmony, not “how to write atonal music,” after all – and this showed he had a musical pedigree originating (first of all) in Brahms, rather than Wagner (the two polarities of late-19th Century Germanic music) and that despite his lack of a great teacher with conservatory training, he actually seemed to know what he was talking about (add some symbol indicating sarcasm).

He had already written a series of piano pieces (particularly the Op. 11 pieces) and songs (especially the song cycle, The Book of the Hanging Gardens, the Five Pieces for Orchestra (Op.16), the dream-like (or nightmarish) monodrama for soprano and orchestra Erwartung (completed in just 17 days), all written by 1909, plus a few more piano pieces, a song and another short opera before he began Pierrot.

I was going to mention something about “the path of tonality” which is, more or less, a way of getting from here (the statement of a key) to there (after various digressions, the return or restatement of that key). Ironically, Erwartung takes place on a path through the dark night-time woods of a dream, but the woman (did she or did she not kill her lover?) cannot find her way (reality).

Most people would imagine atonality as “off the beaten path” and that it is not satisfying in the long run because it lacks this symmetry of statement-digression-and-return that is the basis of tonality.

But would most listeners today (if not those, a hundred years ago) know whether a piece begins in C-Sharp Minor and ends not in C-Sharp Major but D Major like Mahler’s 5th (or going from D Minor to D-flat Major, like his 9th)? And would they care? I don’t believe anyone grouses about Bach’s B Minor Mass not ending in B Minor or B Major.

Looking ahead to what Schoenberg would compose after Pierrot, it’s interesting to realize he completed only one piece (a set of four songs with orchestra) between 1912 and 1920.

With Pierrot, it seems he had reached the limit of where atonality could go – just as he’d been feeling the limits of tonality before 1908. Just as Wagner had felt after writing Tristan – either you go forward or you go back. And if you go forward, you’ll probably want to find another way (or path) so other people can follow you.

In that sense, Schoenberg evolved a “system of writing with twelve tones,” taking the twelve notes of the chromatic scale (rather than the seven notes of a diatonic scale that was long the basis of tonality) and weighing them equally – no hierarchy of tonic, dominant, sub-dominant as we had in Classical Music’s theory of tonality. Chords move in certain ways – they have “functions” in that sense. But not any more: is there another way to organize these sounds?

Debussy was introducing chords that didn’t move at all, in the traditional sense, resolving to other chords, just moving to other chords with no sense of harmonic direction – passages of chords that are “non-functional” and create primarily color rather than harmonic progressions. (One could also get into the whole-tone scale as something else to talk about the de-gravitalization of harmonic tonality since the scale possesses no chord that can serve as a dominant-to-tonic resolution, but I’ve had too many digressions already).

Schoenberg’s approach seems nothing more than the systematization of the all-chromatic, non-tonal music he’d been composing for only four years (1908-1912) into something that had rules and laws and exceptions that, unfortunately, became so rigidly observed by some of his followers, that it became a mechanical substitute for inspiration.

Students taking an Introduction to Music Class who majored in Non-Music often enjoy the discovery of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone “system” – now, universally called “serialism.” It’s like a crossword puzzle; you can figure it out intellectually, fill in the blanks, and if you follow “the rules,” it practically writes itself (no matter what it sounds like). But you don’t sit down to enjoy reading crossword puzzles: you do crossword puzzles – it’s an interactive form of entertainment: no one watches you do a crossword puzzle.

The whole problem of any musical system is getting beyond the system to create, in your own way, Art. Mozart and Beethoven learned rules and delighted in bending and breaking them (often to the consternation of their contemporaries). If they wrote strictly according to the rules, I doubt we’d be performing them any more than we might hear quartets by Kozeluch or operas by Weigl (to mention two popular composers who were their contemporaries).

But it strikes me as odd that a hundred years after Pierrot Lunaire was first heard, it still strikes people as a “difficult” piece. It certainly is an unsettling one – given the nature of the poems he set to the music he wrote – and there would be a decided disconnect between the poems and the music if he wrote it in the style of Puccini (who, incidentally, liked Pierrot when he first heard it).

On the other hand, at that same performance Puccini attended, the director of the local music school complained “if there had been just one single honest triad in the whole piece!”

Schoenberg wrote “Am I to blame for his disappointment?”

Listeners had trouble with Beethoven because he wasn’t Haydn, their pole-star. Then they didn’t like Wagner because he wasn’t Beethoven. Brahms didn’t like Mahler because, basically, he wasn’t Brahms. If you listen to an unfamiliar work (new or not, by whatever definition you choose) but judge it according to what you’re familiar with, anything new doesn’t stand a chance.

Beethoven’s Late Quartets were panned by critics, listeners and performers as the result of his deafness. Even fifty years later, people still had problems accepting them, they sounded so contemporary.

These days, the Late Quartets are held up as a pinnacle of achievement in the quartet literature that has rarely (if ever) been equaled.

Why the change in attitude?

Well, perhaps listening to Wagner and Mahler and Schoenberg in between has helped us realize that what Beethoven was doing wasn’t so different after all?

(One of my favorite bad reviews described a quartet by Milton Babbitt as "what a Late Beethoven Quartet must sound like to a dog." A friend of mine once sent me a postcard from the New Music Festival at Tanglewood of a very distinguished collie sitting on its haunches in the grass with a pipe in its mouth! On the back, my friend wrote "Listening to Late Beethoven Quartets.")

It was interesting, after talking about “innovations” in musical language before a program of Mozart, Beethoven and Lutoslawski with the Philharmonia Quartet Berlin last week at the start of the Market Square Concerts season, and starting off with a “dramatic reading” of the opening paragraphs of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, no one walked out of the performance of the unfamiliar Lutoslawski quartet – just as no one walked out of last season’s concert with the JACK Quartet which included, among other more recent works, Tetris by Iannis Xenakis. In fact, while there were those who didn't enjoy themselves, obviously there were many who did.

Perhaps it’s time, now that we’re well into the 21st Century, that we listen to 20th Century music like the century-old stuff it is?

*** ***** ******** ***** ***

My intent had been to write a historical background leading up to the premiere of Pierrot Lunaire, then do one of those up-close posts I enjoy writing about, whether anybody else ever reads them or not.

But three hours and 2,300 words later, it’s become something else (been there/done that). Instead, here’s an earlier post re-posted with my own adaptation of the translation in preparation for a wonderful performance I’d seen years ago when the contemporary ensemble called eighth blackbird came to Central PA with Lucy Shelton to perform Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire staged, with costumes and action (and memorized!!!), not just as a concert song-cycle for soprano and chamber ensemble.

You can read that post, here.

One of the delights of that performance, by the way, was watching the audience. A few rows in front of me were several “older ladies” who looked like they might have been bused in from an “assisted living” center for a cultural night out, probably not knowing what they were getting into.

Throughout the Schoenberg, I could see their faces: expressions of wonder, of laughter, of fear (some of it can be very scary) and in the end of enjoyment as they heartily applauded the performers.

Incidentally, having a little fun with Schoenberg, here's a link to my serial novel (in twelve chapters) about a serial killer called The Schoenberg Code.

- Dick Strawser