|

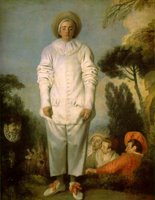

| Watteau's Pierrot, 1719 |

It’s not really a story, though – perhaps it’s more about story-telling. The way the story is told and the music Schoenberg composed to tell it have become one of the most significant works in the 20th Century.

Today marks the 100th Anniversary of its world premiere.

It’s originally a cross between a cabaret entertainment and the old “melodrama” tradition – spoken word accompanied by music – something that’s fallen out of favor in the last few generations. It’s not just “narration with music,” like “Peter & the Wolf” or “The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.” The composer sets the text by writing out the spoken rhythms which very often creates a rather unnatural sounding extension of the spoken voice. What Schoenberg chose to do was create a style of vocal delivery that became something of the rage for a few decades: though it gradually fell out of fashion, if handled right, it can still be more dramatic than just plain singing or speaking (or something to make people giggle because they think it just sounds silly). And if it doesn’t seem to have much connection with today’s attitudes in music, think about rap!

In 1912, Arnold Schoenberg set 21 poems by the Belgian poet Albert Giraud who composed 50 poems inspired by the old commedia del’arte figure of Pierrot the Clown in 1884.

“Each short poem then describes a situation or scenario, with Giraud's imagination running riot: now Pierrot is preparing himself for a night on the town; now he is comparing the moon to an omelette as he stirs the pan and tosses the eggy mixture into the night sky; now Cassander is railing at Pierrot to stop scraping on his viol; now Harlequin is parading his latest colourful outfit, or bribing Colombine's chaperone to get an evening with her; now Pierrot is hanging himself with his own robe.....”

Giraud’s poems are in a specific old-fashioned French style called a “rondeau” which consists of thirteen lines where the first two lines are repeated at the end of the second stanza and the first line is repeated at the end of the third. Schoenberg divides his piece into three equal parts of seven poems each.

> In Part I, Pierrot, intoxicated by the moon, dreams of love or lust, with repeated images of blood and illness.

> Part II places us in a violent nightmare world of adventure and blasphemy.

> In Part III, highlighted by his prankish attacks on the hapless bald-headed Cassander, he journeys home to Bergamo, haunted by nostalgic thoughts of a fabled past with a happy ending after all.

It becomes fairly clear these are “fantastical” stories, full of strange psychological symbols (the antidote to Realism, Symbolism became all the rage in France at the end of the 19th Century) drifting in and out like a nightmare careening from one image to the next. The color red recurs constantly – from Pierrot’s make-up table to a drop of blood which soon flows with constant reference to bleeding, to blood-red rubies, even to something as simple as a short red skirt worn by an old woman who “loves Pierrot till it hurts.” The moon and moon-beams, logically, are frequent images, often frightening ones (the moonbeams reflecting off a Turkish scimitar which Pierrot imagines will behead him), inspiring thoughts you might not think in broad daylight (not to mention other lunacy: when do our dreams turn most to nightmares?) along with the color black, whether simply the void of night-time or the realm of fear and the unknown.

When I was looking for some on-line sites that might include reasonable English translations of the whole texts, I was surprised to find nothing that I could really link you to. Without wanting to risk any copyright infringement by simply copying into this post someone else’s translation, I decided at the last minute to do my own. They’re not meant to be a performing translation nor are they exactly literal – though in some cases I found some of the standard English ones do not seem to convey the original meaning, necessarily – but they’ll give you an idea of each poem’s content, which is all I’m concerned about.

PART ONE

1. Moondrunk

The wine we drink through the eyes

Flows nightly from the moon in torrents,

Like a spring tide

Overflowing the far horizon.

Terrible and sweet desires

Drift in floods without number!

The wine we drink through the eyes

Flows nightly from the moon in torrents.

The poet, driven by devotion,

Befuddled by the holy drink,

Raises to Heaven his ecstatic head

And reeling, slurps up and guzzles

The wine we drink through the eyes.

2. Colombine

The moonlight’s pale blossoms,

The white and wondrous roses,

Bloom at night in July –

O could I pluck just one!

To ease my heavy sorrow,

I search in the dark current for

The moonlight’s pale blossoms,

The white and wondrous roses.

All my longings would be stilled,

If I could, like in the secret fables,

Scatter upon your brown hair

The moonlight’s pale blossoms.

3. The Dandy

With a fantastical light-beam

The moon illuminates the crystal flask

Upon the black, highly sacred wash-stand

Of the taciturn dandy of Bergamo.

In the sonorous bronze basin

The fountain’s metallic tone laughs brightly.

With a fantastical light-beam

The moon illuminates the crystal flask.

Pierrot, with waxen countenance,

Stands musingly and thinks:

How will he make himself up today?

He rejects the red and Oriental green

And paints his face in the latest fashion

With a fantastical moonbeam.

4. A Pallid Washerwoman

A pallid washerwoman

Washes faded silks at night-time,

Naked, silver-white arms

Stretch down into the flow.

Through the clearing gentles breezes

Softly ruffle the stream.

A pallid washerwoman

Washes faded silks at night-time.

And the placid Maid of Heaven,

By the branches softly fondled,

Spreads out on the dusky meadows

Her moonbeam-woven linens –

A pallid washerwoman.

5. Chopin’s Waltz

Like a faint drop of blood

That stains the lips of an invalid,

So these tones contain

A morbid and destructive charm.

Wild passionate harmonies

Disturb the icy dream’s distress –

Like a faint drop of blood

That stains the lips of an invalid.

Fierce and joyful, sweet and yearning

Melancholic somber waltzes,

You never come to me

Through the senses!

Cling to my thoughts

Like a faint drop of blood.

6. Madonna

Rise, O Mother of all Sorrows,

From the altar of my verses.

Blood flows from your meager bosom

Pierced by a sword-like frenzy.

Thy ever-bleeding wounds

Are like eyes, red and open.

Rise, O Mother of all Sorrows,

From the altar of my verses.

In thy lacerated hands

You hold the body of your Son,

Revealing Him to all Mankind –

Yet the glance of Men avoids you,

O Mother of all Sorrows.

7. The Sick Moon

You ailing, death-sick moon,

Upon Heaven’s blackened pillow,

Your gaze, so fevered, wide-eyed,

Lures me like an alien melody.

With unrequited love-pains you die

Of longing, smothered,

You ailing, death-sick moon

Upon Heaven’s blackened pillow.

The lover, who inflamed with desire

Creeps without thinking to his beloved,

Delights in your plays of light –

Your pale blood borne of anguish,

You ailing, death-sick moon.

PART TWO

8. Night

Sinister black giant butterflies

Have killed the shining sun.

A sealed book of magic,

The horizon sleeps – silenced.

From the mists of forgotten depths

Rises a scent, murdering memory!

Sinister black giant butterflies

Have killed the shining sun.

And from Heaven toward the earth

They descend with beating wings,

Invisible monsters,

To the hearts of men below…

Sinister black giant butterflies.

9. Prayer to Pierrot

Pierrot! My laughter I’ve unlearnt!

The picture of brilliance dissolves – dissolves!

Black flies the flags from my mast, now.

Pierrot! My laughter I’ve unlearnt!

O give me once again, Healer of the Soul,

Snowman of lyrics, Serene Highness of Moonlight,

Pierrot – my laughter!

10. Theft

Red-gleaming princely rubies,

Bloody drops of ancient glories,

Slumber in the coffins of the dead,

Buried in the graves.

At night, with his companions

Pierrot descends to rob

Red-gleaming princely rubies,

Bloody drops of ancient glories.

Yet there, with every hair on end,

Fear turns them to statues:

Through the darkness – like eyes! –

Staring from the coffins of the dead,

Red-gleaming princely rubies.

11. Red Mass

At gruesome grim communion,

By blinding rays of gold,

By flickering candlelight

Comes to the altar – Pierrot!

His hand, dedicated to God,

Tears the priest’s vestments

At gruesome grim communion,

By blinding rays of gold.

With signs of benediction,

He shows the trembling souls

The dripping red Host:

His heart in bloody fingers –

At gruesome grim communion.

12. Gallows Song

The haggard harlot

With scrawny neck

Will be the last

Of his lovers.

And in his brain

She sticks like a needle,

The haggard harlot

With scrawny neck.

Skinny as a pine-tree,

A pigtail ‘round her neck

She happily strangles

The rascal with it,

The haggard harlot!

13. Beheading

The moon, a shining Turkish scimitar

On the black silk cushions,

Hangs large – like a threat

Through the sorrow-darkened night.

Pierrot roams without rest

And stares ahead in deadly fear

At the moon, the shining Turkish scimitar

On the black silk cushions.

His knees are shaking,

He faints and collapses.

He fancies: hissing, punishing, already

It comes down upon his sinful neck,

The moon, a shining Turkish scimitar.

14. The Crosses

Holy crosses are the verses

Where poets bleed silently,

Blinded by the vultures

Flocking ‘round in ghostly swarms.

On their bodies, swords have feasted

Flaunting their scarlet blood.

Holy crosses are the verses

Where poets bleed silently.

Dead the head – the hair stiff –

Distant, faint the rabble’s cry.

Slowly sinks the sun below,

A crimson royal crown –

Holy crosses are the verses.

PART THREE

15. Nostalgia

Sweet lamenting, crystal sighing

From the old Italian pantomime

Sadly asks: Why has Pierrot become so wooden,

So modern and sentimental?

And it echoes through the desert of his heart,

Muted echoes through all his senses.

Sweet lamenting, crystal sighing

From the old Italian pantomime.

Then Pierrot forgets his tragic manner!

Through the fiery moonlight,

Through the radiant flood – his longing swells,

Soaring boldly home to heaven,

Sweet lamenting, crystal sighing!

16. Atrocity!

Into the shiny skull of Cassander,

Who fills the air with shrieks,

Pierrot bores with false kindness –

Sweetly – a cranium driller!

And then presses with his finger

His genuine Turkish tobacco

Into the shiny skull of Cassander,

Who fills the air with shrieks!

Then screwing a cherry pipe-stem

Firmly into the polished surface,

He leisurely smokes and puffs away

At his genuine Turkish tobacco

In the shiny skull of Cassander!

17. Parody

Knitting needles, bright and twinkling

In her graying hair,

The Duenna sits mumbling

In her little crimson skirt.

She waits in the arbor;

She loves Pierrot till it hurts,

Knitting needles, bright and twinkling

In her graying hair.

Then suddenly – hark! – a whisper!

A puff of wind chuckles softly:

The moon, that wicked mocker,

Mimics with his moonbeams –

Knitting needles, bright and twinkling.

18. The Moonspeck

A snowy speck of shining moon

On the back of his black frock-coat,

So Pierrot sets out one languid evening,

Seeking fortune and adventure.

Suddenly, something’s wrong with his appearance,

He looks around till he finds it –

A snowy speck of shining moon

On the back of his black frock-coat.

Drat, he thinks, a fleck of plaster!

He wipes and wipes but can’t make it vanish!

And on he goes, his pleasure ruined;

He rubs and rubs till early morning

At a snowy speck of shining moon.

19. Serenade

With a grotesquely giant bow,

Pierrot scrapes on his viola;

Like a stork standing on one leg,

He sadly plucks a pizzicato.

Suddenly, here comes Cassander,

Fuming at the night-time virtuoso.

With a grotesquely giant bow,

Pierrot scrapes on his viola.

Then he throws the viola aside:

With his delicate left hand

He grabs the bald-headed guy by the collar,

Dreamily playing on his skull

With a grotesquely giant bow.

20. Homeward Journey (Barcarolle)

The moonbeam is the rudder,

A water lily as his boat;

Pierrot travels southward

With a good wind behind his sails.

The stream hums low scales

And rocks the fragile craft.

The moonbeam is the rudder,

A water lily as his boat.

To Bergamo, his homeland,

At last Pierrot returns;

Soft shimmering already

In the east the green horizon.

The moonbeam is the rudder.

21. O Ancient Scent

O ancient scent from fairy-tale time,

Intoxicate my senses!

A foolish bunch of rogues

Whirr through the gentle air.

Cheerfully I’m glad to return

To long-neglected pleasures:

O ancient scent from fairy-tale time,

Intoxicate my senses!

All my gloom’s dispelled;

From my sun-surrounded window

I gladly view the lovely world

And dream beyond the wide horizon…

O ancient scent from fairy-tale time…

(— translations and paraphrases by Richard Alan Strawser)

In 1912, the Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg was commissioned by an actress who’d studied voice with the wife of Richard Wagner, Cosima, even though she was not really a singer: she wanted a work for speaker and piano, selecting texts from Giraud’s poems translated into German. Schoenberg chose 21 of them – as he called it, “three times seven poems” – and the accompaniment grew to include a flutist (who also plays the piccolo), a clarinetist (who also plays the bass clarinet), a violinist (who also plays the viola) and a cellist, in addition to the piano. Each of Schoenberg’s settings uses a different combination of instruments so the texture and sounds are constantly varied.

This combination of instrumentalists – actually the first such chamber ensemble to mix strings and woodwinds with the piano – became such a popular combination in the 20th Century (with or without the speaker/singer, and often adding a percussionist), it’s became standardized simply as “the Pierrot ensemble.” Like the old Baroque concept of the “basso continuo” which consisted of an accompanying harmony-playing instrument (a harpsichord or organ, maybe a lute) with a low-register melodic instrument (like a cello or a bassoon) emphasizing the bass-line, the percussion instruments become an extension of the piano (which is often used more as a percussion instrument, since hammers strike strings similar to ways a drummer uses mallets to hit a xylophone, for instance), supplying not so much fuller harmonies (as in the Baroque) but greater variety of rhythms and colors, two musical elements that became more prominent in the 20th Century. (If you want to consider this analogy further, look at the standard jazz combination of a melody instrument – saxophone? – with piano, augmented by double bass and a drummer; what about rock bands with their lead singer, various guitarists playing harmony, a keyboard organ or synthesizer a bass guitarist and a drummer – and of course the back-up singers who, with their choreography, augment the visual element of the performance, with or without the light show! But I digress, kind of...)

Schoenberg’s famous (or infamous) “sprechstimme” – literally “speak voice” or, better, “speak-singing” – takes the singer into a more declaimed delivery style (or the actor into a more sung delivery style) that is really a combination of the two. Ms. Shelton described the exaggerated sound as opening a world of colors and registers that, while maybe sounding laughable when spoken in conversation, turn the voice into an instrument of constant variety. In Schoenberg’s sketches, he noted the exact pitches but instead of using traditional note-heads, marked it with an X. The rhythms are exact and work directly into the complex textures of the music with the other musicians, but he intends, really, the pitches only to be “implied” – directing the “speaker” to hold the note only briefly before falling away from it “in the manner of speaking.” In this way, the performer can use the pitches as a suggestion for the register of the voice or she can sing the pitches as written (Ms. Shelton said a recent recording by Pierre Boulez – I suspect the DG one with Christine Schafer in which he asked her to be truer to the written pitches “just because I think he wanted to hear what it sounded like” with the original pitches).

You can also go to the Arnold Schoenberg Juke-Box (I’m not making that up) and listen on-line to each song individually. The juke-box, here, is a great resource whether you’re curious about Schoenberg’s music or are quite familiar with it and just want to – you know – listen to it at your computer while you’re sitting in your cubicle.

Like any ground-breaking work, “Pierrot lunaire” is surrounded by controversy, even today: some people just hate it. That’s probably because they can’t get past the fact that it’s not Beethoven and you can’t hum it like Puccini – or maybe they’re too uncomfortable thinking about Pierrot’s nightmare world (or don’t want to admit they are). The musical style is called “atonal” because it’s not in the traditional mix of keys or tonalities we associate with classical music of previous centuries – no D Major or A Minor – and freely uses all twelve notes of the chromatic scale to create what (by comparison) you’d call “dissonance” (just to clarify, this is not the same as Schoenberg’s “twelve-tone” technique which would come about almost a decade later, a more complex way of organizing those twelve pitches into something comparable to the tonal system). Now, if you’ve read the poems and you’ve figured out what’s going on behind these fractured fairy-tales, a musical style as disembodied as the literary style would seem perhaps more appropriate to the “psychological disconnect.” Granted, one of the problems of this style is that it does “weird and anxious” better than it can do other moods – though the very opening of “Pierrot” just sparkles with reflected moonlight that is neither weird nor anxious – but as far as this piece is concerned, the style matches the words like a glove (maybe an ink-black glove splattered with drops of blood, but still, a glove).

And just because I found it while googling, did you know that Björk performed “Pierrot Lunaire” at a music festival in Switzerland in 1996? The conductor was Kent Nagano and they rehearsed for three months – but the recording was never released. Talk about “cross-over”!! There are two sound-clips here from the concert (badly recorded and probably piratical) of the magical opening and of the Gallows Song (the harlot with the strangulous pigtail) that just makes you wonder...

Dick Strawser

Thank you for this. I found it fascinating and very informative.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much, especially for your translation. I am going to the Morgan Library (NYC)now, to hear this gorgeous, sensational work. Shela Xoregos

ReplyDeleteThanks for a great translation.

ReplyDelete