In the week since my mother’s death, I have found boxes of pictures that I knew she had been sorting through and sometimes labeling, scanning pictures to e-mail to my brother and I or her sister on the computer we’d gotten her when she turned 80, including lots of photos from the 1920s to the 1940s as well as her parents’ wedding picture from 1911 and family photographs of her mother taken before they left England.

There were some with vague historical details that I only remember from what she had told me, then: a heavily bearded gentleman was her grandfather whom no one in the family seemed to know much about. All the known pictures of her grandmother show her in “widow’s black” which leads us to believe he died when she was not yet middle-aged. By association, she must be the young woman with her hand leaning demurely on her older husband’s shoulder in a carefully choreographed family portrait taken after his own father’s death, his mother (my great-great-grandmother) seated amidst her children looking very much like Queen Victoria who spent much of her own life wearing widow’s black. Looking at it, I’m not sure I can explain why I dated this picture to the 1870s, now, but it’s the start of a long line of family photographs – using this old technology – that ends with a photograph taken a year or so ago of my mother, then in her mid-80s, with her great-granddaughter. I will scan many of these onto a CD and hope that, when she grows up, my great-niece will have the technology available to view a CD-Rom, if looking at the sadness on the face of her great-great-great-great grandmother (whose name I do not even know) will connect her with a past she never knew existed.

But I also found other boxes that I had never seen before and which maybe Mother had forgotten she’d placed on a top shelf in a closet. Many of them were recognizable – this aunt, that uncle, though taken before I was born – and others may not really matter as long as I can tell they are part of her father’s large collection of friends and siblings.

In an album that had only a few pages of mounted photographs which my father had generously captioned – followed by several pages with fistfuls of unsorted, usually uncaptioned photos intended for later inclusion – I saw a series taken on a mild December day in 1940 with my Uncle Marlin who had died later in World War II. There was my mother, not quite 10 months a bride, standing with my uncle who looked proud and spiffy in his army uniform. Then I saw my dad in his army uniform and thought, “wait, he wasn’t in the army” before I realized he – and then my Uncle Bob too – were all having their pictures taken wearing Uncle Marlin’s jacket!

Some lack dates which might be helpful, others lack clues if you don’t know what to look for (one couple’s wedding photo she helpfully labeled “not a clue”).

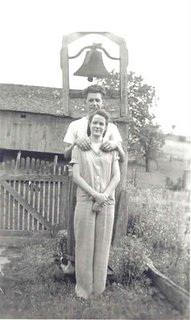

It was good to find pictures of her that erase the pain of seeing her those final days. It was amazing to read through old calendars, some stored in boxes in her office (on a desk that her father had bought when he graduated from high school in 1905) that were kind of like journals where I could fill in the details, knowing an anecdote from the family history or discovering a day in June marked “1st Anniv of 1st Date” with my dad and pictures taken on her grandfather’s farm (see photo at left) in upper Dauphin County.

It was good to find pictures of her that erase the pain of seeing her those final days. It was amazing to read through old calendars, some stored in boxes in her office (on a desk that her father had bought when he graduated from high school in 1905) that were kind of like journals where I could fill in the details, knowing an anecdote from the family history or discovering a day in June marked “1st Anniv of 1st Date” with my dad and pictures taken on her grandfather’s farm (see photo at left) in upper Dauphin County. One anecdote I knew from early in my childhood: how Dad got his first Hammond organ. Well, not really his... He had played the piano since he was in grade school – he had perfect pitch but never took lessons from anyone, just figuring everything out by ear – and he learned how to play the organ much the same way during The War, sneaking into the base’s chapel though he was primarily playing the popular songs of the day to entertain his friends and anyone who’d listen. After the war, a friend of his, Jack, was building his own house and the Hammond organ he’d ordered was going to be delivered before the house was ready: would my folks mind if he’d have it delivered to their place in Paxtang so he wouldn’t lose the option on it (it would go to the next person on the list and he’d be bumped to the bottom, otherwise). Well, sure! Paging through a 1947-1948 ‘engagement’ book, my mother wrote down the day Jack’s Hammond was delivered (see photo at right). Later that summer, my dad made his debut at the Pueblo, a night-spot in Harrisburg, as a “cocktail organist” (the second night, she noted, went better than the first; a few days later, she also mentions his first tip, $1.00). Throughout the book were annotations of “Jack over for dinner” or “dinner at Jack’s” and frequent games of pinochle with Jack and other friends. On March 17th, 1948, she writes “Our 8th Wedding Anniversary.”

One anecdote I knew from early in my childhood: how Dad got his first Hammond organ. Well, not really his... He had played the piano since he was in grade school – he had perfect pitch but never took lessons from anyone, just figuring everything out by ear – and he learned how to play the organ much the same way during The War, sneaking into the base’s chapel though he was primarily playing the popular songs of the day to entertain his friends and anyone who’d listen. After the war, a friend of his, Jack, was building his own house and the Hammond organ he’d ordered was going to be delivered before the house was ready: would my folks mind if he’d have it delivered to their place in Paxtang so he wouldn’t lose the option on it (it would go to the next person on the list and he’d be bumped to the bottom, otherwise). Well, sure! Paging through a 1947-1948 ‘engagement’ book, my mother wrote down the day Jack’s Hammond was delivered (see photo at right). Later that summer, my dad made his debut at the Pueblo, a night-spot in Harrisburg, as a “cocktail organist” (the second night, she noted, went better than the first; a few days later, she also mentions his first tip, $1.00). Throughout the book were annotations of “Jack over for dinner” or “dinner at Jack’s” and frequent games of pinochle with Jack and other friends. On March 17th, 1948, she writes “Our 8th Wedding Anniversary.”There was a box of her father’s early record-keeping, too: rent receipts he’d paid for apartments before they bought their first house the year my mother was born ($15/month rent – not bad) or lists of furniture they’d bought (including a piano for $420), lists of books he’d read, lists of facts he thought were important to remember, and a string of medallions he wore as a member of the Philadelphia branch of the Knights of Malta in 1918. Ironically, I realized, last Friday sitting there amidst these boxes of papers and pictures we were sorting through on the floor, looking up at the desk I often looked up at when I was a child, that that Friday was my grandfather’s birthday and so we went out for dinner to celebrate the past.

My mother had become a keeper of lists herself: the gene is apparently inherited from her father. There are ledger books with every book she read since 1985 when my father died and piles of books that she’d not yet logged but which had post-it notes on them indicating when she’d finished reading them. There’s a ledger itemizing every piece of clothing she bought between 1984 and 1994. There are bundles of notes listing every visitor and phone call she received and made since 1993 (and I suspect I will find previous years tucked away somewhere else). Her more recent calendars, while devoid of highlights like she noted in 1947, may have contained less interesting information – the high and low temperatures for every day or when the Lawn Guy mowed the grass (highlighted in green). She was, if anything, a meticulously organized packrat. I have inherited the packrat gene but unfortunately not her organizational skills: my laissez-faire approach to clutter is something I inherited from my dad.

There are bundles of letters still to be sorted and read, though fewer than I would’ve thought. But that is for another day. In this age of e-mail and instant messaging – and yes, I found print-outs my mother had made of several of the chat sessions we’d had when she first got her computer – what will be left for families to reminisce over in the future? I can hold a 130-year-old photograph in my hand and feel the connection with my family’s distant English roots, but what of all those jpg’s locked in some already out-dated computer software program or storage format? What about all those reel-to-reel audio tapes she’d made from the radio broadcasts when my dad had a weekly 15-minute show, live from the Blue Mountain Hotel in the mid-1950s? We had often talked about trying to resurrect them so she could hear them again before she died, but it kept getting put off, too involved a process, perhaps, and even at 87½ we still felt there was time.

One of my rituals these past 15 years or so was to call my mother, however often I may have talked to her the rest of the week, Sunday nights following the 11:00 news. Even though she was expecting it, she said it always made her jump when the phone rang and she would worry if I was a few minutes late. We would talk, maybe, for an hour or more, both of us night-owls (I was born, according to my baby calendar in which she annotated every event and illness that first year, at 2:58 a.m.). But tonight was the first Sunday night since the funeral that I know she’s not there for me to call on the phone.

Years ago, I had found a quote – mentioned in one of May Sarton’s journals – attributed to St. John Chrysostom:

He whom we have loved and lost

Is no longer where he once was.

He is now wherever we are.

And I also know that, after 21 years, my mother and my father are together again. And these two understandings help me considerably in dealing with her loss.

-- Dr. Dick

Photo credits: all from family collections - (1) Mother in a black dress taken by my dad in early-1940s; (2) Mom & Dad on the Hartman Farm in Williamstown PA, 1939, the year before they married; (3) My dad, Norm Strawser, playing Jack's Hammond organ in the living room of our house in Paxtang (two years before I was born); (4) Mom & Dad in 1944, a photograph I found in her wallet the day she died, February 23rd, 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment