Of course, it also helped to feel brighter and refreshed the next morning, too (despite the fact I was up till 3am blogging), even though I still would not consider myself a morning person. Over the years, I find I am less able to do creative work at night – even blogging goes more smoothly in the morning, something I dislike because it takes away so much of what little creative time there is in my schedule. Working second shift at the station, I often find programming and research there can go much better after I’m off the air, but that uses, I guess, a different part of the brain, though in a way it’s creative, too, just in a different way.

Anyway, on Saturday morning, things in general just looked better: not to so much what I’d written and scribbled over and crossed out the night before, but that I now saw things that I could do and – wait, that looks kind of interesting, so if I... YES! That note, that’s the one – it works! I must have filled three pages with attempts at finding that note – and all I did, really, was take one note in this chord and exchange it for one note in that chord: not only did it sound better, the harmonies it created worked much better (or rather, worked period!) theoretically as well as just sounded better.

(My apologies for all the technical mumble-jumble that follows: I know it’s about as exciting as reading computer programming texts for non-Geeks or all those blah-blah EULAs or whatever they’re called – you know, the on-line agreements for your downloaded free software that you never scroll all the way down to find out that the third Tuesday of every month is your day to go clean out Bill Gates’ cat-litter boxes, right? But bear with me: if it’s not your thing and your eyes are already rolling, check in later for another post.)

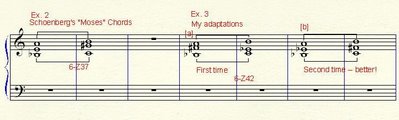

What I’d started with was this, the opening chords from the 2003 sketch:

It doesn’t really do anything and doesn’t present a lot of potential. It may have been one reason why I suddenly stopped working on it a couple of weeks later: it wasn’t going anywhere and I didn’t feel like I wanted to take the time to sort it out. At the time, I was working on the Symphony and what I was looking for was some seasonal relaxation, not another major complication!

It doesn’t really do anything and doesn’t present a lot of potential. It may have been one reason why I suddenly stopped working on it a couple of weeks later: it wasn’t going anywhere and I didn’t feel like I wanted to take the time to sort it out. At the time, I was working on the Symphony and what I was looking for was some seasonal relaxation, not another major complication!Thinking back to the magical sound that opens one of my favorite works (and one that I first discovered in high school), I decided to get out my score of Arnold Schoenberg’s “Moses und Aron” (yes, after going into New York City to see two different productions at the Met and at City Opera, I broke down and bought the full score, convinced that $100, these days, really was a bargain for such a masterpiece...) and check out the first two chords which represent the “Voice of God” calling out of the Burning Bush.

They’re just two parallel major 7ths a whole step apart: it’s the middle note that defines them, gives them their “color.”

They’re just two parallel major 7ths a whole step apart: it’s the middle note that defines them, gives them their “color.”I didn’t want to use the same ones (and wanted them to start on different pitches, anyway), just use them as a kind of reference point and a kind of ‘hommage’ – my first attempt (see ex.3a above) made a subtle alteration: the first of the two Schoenberg chords consists of 4ths – well, officially a Perfect 5th which is the inversion of a Perfect 4th and a tritone or augmented 4th (the “Devil in Music” as they always say – at least that’s how they described it centuries ago) – and the second one is built on 3rds, basically: a minor 3rd below the top note, but also a minor 6th (the inversion of a Major 3rd) above the lower note. My first chords are just based on 3rds – a 3rd below the top note and then, symmetrically, a 3rd above the bottom note for the second chord. Eh... However, if I just switch those two inner notes, I get two very different sonorities, going back to the first of Schoenberg’s chords: this time, they’re both based on Perfect 4ths and Tritones, and have a more open and, I thought, more interesting sonority for what I was looking for.

That was when things started to roll.

Anyway, I’m writing a Christmas Piece, okay? This is supposed to be, I guess, the Voice of God sending the Angel Gabriel to Nazareth to tell Mary the Good News. So how can I have intervals like “The Devil in Music” in God’s Chords? Hmmmm...

Now, it’s curious, but composers have often dealt with symbolism in their selections of chords and pitches and keys – I mentioned in the last post the idea of using E-flat and A Major chords because of the three flats or sharps in their respective key signatures representing The Trinity and I have to admit that’s really simplistic: I mean, shouldn’t all religious pieces then be in either E-flat or A Major? Regardless, I thought I should use something a little less dependent on the tritone, at least for these particular chords.

I also wanted to find some kind of “contrapuntal” symmetry beyond just two chords sitting there on a piece of paper. It’s amazing, when you think about it, how those two chords from the Burning Bush actually ignited Schoenberg's whole opera, just from those six notes – well, okay, not a whole opera, since he never figured out how to end the opera: he stopped working at it after the end of the 2nd Act, but that’s another issue.

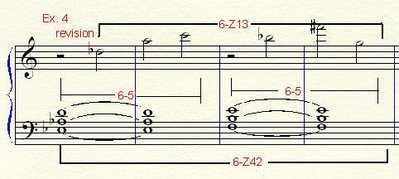

So I have two chords (now transposed to begin on E-flat in the bass) – six pitches, which is a hexachord of a particular number of notes and intervals. Allen Forte labels this one 6-Z42. Its complement – the other six pitches – will either be the inversion of the first six or some other form from a closely-related hexachord (represented in Forte’s language as a Z-related pair), in this case, 6-Z13. By arranging these six notes into two pairs of three – two sub-motives or linear cells – I got an arpeggiated chord similar to the harmony: instead of perfect 4ths & tritones, it’s a major 7th with a minor third below the top note and a major 7th with a minor third above the lower note: now I have both sonorities from Schoenberg’s Burning Bush. Curiously, I found that the linear aspect of each set produced 6-Z13/42 but looking harmonically at it, the first 3 notes of the upper line and the first chord produced a different set: 6-5. Because they’re symmetrical, the second 3 notes and its chord is the first one’s complement.

Now, one set of six notes and some other set of six notes could be related by the number of pitches or the number of intervals they have in common – or perhaps, don’t have in common. In this case, the relationship between 6-5 and 6-Z13/42 is kind of weak. I wanted to find something stronger. Or more outstanding.

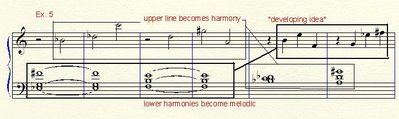

Now, one set of six notes and some other set of six notes could be related by the number of pitches or the number of intervals they have in common – or perhaps, don’t have in common. In this case, the relationship between 6-5 and 6-Z13/42 is kind of weak. I wanted to find something stronger. Or more outstanding.A few transfigurations later and I’ve changed the opening chords a little and found different notes for the upper line. But now it started evolving into other possibilities: Schoenberg used to call his style a “continuous variation” where everything grows organically out of a set of notes, one way or another. In this next example, I found I could take the six notes of the harmony (lower line) and stretch them out linearly in the 2nd half of the example (ignore the rhythms, it was only for spacing), and then also take the first half’s upper line and bunch them together in three-note chords. They look pretty different from each other but they’re really “the same.” This is one way a composer can get variety and yet still maintain “unity.” On a less artistic level, we might just call it “getting more mileage.”

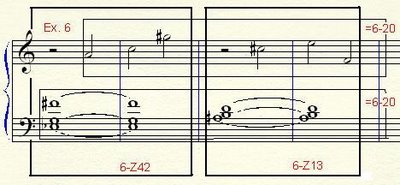

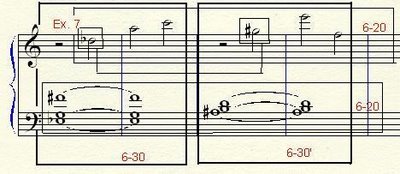

Now, another transformation (see below) shows this contrapuntal harmony/linear thing: while the vertical analysis of the 12 pitches is still a form of 6-Z13/42, the linear analysis – the upper line and then the lower line – create a new set, 6-20.

Now, another transformation (see below) shows this contrapuntal harmony/linear thing: while the vertical analysis of the 12 pitches is still a form of 6-Z13/42, the linear analysis – the upper line and then the lower line – create a new set, 6-20.This is a very curious set. First of all, most of these groupings of pitches can be transposed to start on any note of the chromatic scale, each of which can, usually, be inverted to create a slightly different collection. But here, there are only four such transpositions possible with 6-20 before it starts duplicating itself. This sense of limitation intrigued me: more intriguing was the fact it’s almost entirely made up of major and minor thirds and minor (but not major) seconds – and no tritones! It is a set that is also known as “Genus tertium” which basically means “Third Race” but which I was looking at (since it seems to do this on its own) as a “generator of thirds,” which is basically what I liked about it: the symbolism of the Trinity and the fact it had no “devil in the music.”

But the relation between 6-Z13/42 and 6-20 was even weaker than it was with 6-5. Could I find something better? Then I arbitrarily took one pitch in one segment and interchanged it with one pitch in the other segment and got this:

But the relation between 6-Z13/42 and 6-20 was even weaker than it was with 6-5. Could I find something better? Then I arbitrarily took one pitch in one segment and interchanged it with one pitch in the other segment and got this: ...which doesn’t seem vastly different. But it creates not only a different vertical sonority, it creates a set with a much more striking relationship with the linear sonority, 6-20. Now, 6-30, the new set, is one that’s closely related to 6-Z13/42, but what I found so interesting was that there is an almost minimal amount of pitches and intervals in common between these two sets. It struck me as odd, in my naive way of looking at things, to think that two sets that are hardly related at all could actually coexist in the same musical passage.

...which doesn’t seem vastly different. But it creates not only a different vertical sonority, it creates a set with a much more striking relationship with the linear sonority, 6-20. Now, 6-30, the new set, is one that’s closely related to 6-Z13/42, but what I found so interesting was that there is an almost minimal amount of pitches and intervals in common between these two sets. It struck me as odd, in my naive way of looking at things, to think that two sets that are hardly related at all could actually coexist in the same musical passage.But this was what got me going: 6-20 was one principal set with its own intervalic sonorities, and 6-30 was another one which, if you look carefully, consists of three tritones! The D-flat in the upper voice & the G in the first chord; the A & the E-flat in the bass; the C and the F-sharp. So now I had a new symbolism to go by: 6-20 was my spiritual realm (if not specifically God’s Voice) and 6-30 was my earthly realm (if only to have God’s Word [or Music] made flesh).

And from there, I was scribbling away.

Now granted, after an 8-hour day on Saturday and a nearly 10-hour day composing on Sunday – including a successful late-night shift for two hours before midnight – and a less successful but still productive day on Monday, you’d think I’d have more than about 28 measures done by the time I had to go back to work at the end of my vacation Tuesday afternoon. But I prefer to judge it on the quality of that productivity rather than its quantity and the realization that, whether a listener could hear some of these relationships or not (it’s arguable that most listeners today are aware of the fairly obvious ones in traditional tonal music whether they’re listening to Beethoven or the Beatles), this makes it inherently a stronger (if not a better) piece, one that sounds better to me and one that makes more theoretic or logical sense, as well.

If nothing else, the past few days have been exciting just to realize how quickly I was able to get myself, somehow, over the hump that was so depressing on Thursday night when I was almost ready to chuck the whole piece (again). But a little more perspiration helped ignite a little bit of inspiration and I’m pretty happy with what I’ve done so far, 28 measures (just shy of 2 minutes) all coming out of those first six notes.

And just in time: I wanted to use this week’s vacation to get a good strong start on this new piece, whether I finish it in six weeks or six months. I needed to get this much down now because, as I mentioned before, the upstairs apartment has been empty for almost a month. Who knows who the new neighbors will be, if their schedule will work with mine so I can compose uninterrupted or without being self-conscious of disturbing them (what a treat to think “It’s midnight, but I can go compose at the piano now because there’s no one upstairs to worry about waking up!”). The “For Rent” sign came down today: I have no idea who it will be or when they’ll move in, but at least I got a good week’s worth of work in beforehand.

And tomorrow is another day: at least I can still work in the mornings, for a while longer.

No comments:

Post a Comment