To anybody who's ever been a music student and their teachers everywhere, some Christmas Cheer for this holiday break (something I presented to my own theory students long ago in a galaxy far, far away):

On the first day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

a mess in the figured bass.

On the second day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the third day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the fourth day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the fifth day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the sixth day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

Six foul inversions, FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the seventh day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

seven rising sevenths, six foul inversions, FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the eighth day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

eight bad suspensions, seven rising sevenths, six foul inversions,

FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the ninth day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

nine tenors screaming, eight bad suspensions, seven rising sevenths, six foul inversions,

FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the tenth day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

ten altos droning, nine tenors screaming, eight bad suspensions, seven rising sevenths, six foul inversions,

FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the eleventh day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

eleven basses leaping, ten altos droning, nine tenors screaming, eight bad suspensions, seven rising sevenths, six foul inversions,

FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

On the twelfth day of Christmas, my students gave to me:

twelve rotten discords, eleven basses leaping, ten altos droning, nine tenors screaming, eight bad suspensions, seven rising sevenths, six foul inversions,

FIVE PARALLEL FIFTHS!!!!!

four tritones, three French sixths, two doubled thirds...

and a mess in the figured bass.

Merry Christmas, everybody!

Monday, December 25, 2006

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Christmas Project 3: Ave Maria

With a few days before Christmas, composition has slowed down considerably, unfortunately, now that I’m back to work, but I managed to finish one layer of the opening section of this “Christmas Project” of mine I’ve been posting about, otherwise known generically as “A Christmas Story” for lack of a better working title (see previous two posts). There’s a narration (sung by a tenor soloist) which is one line, and there’s the voice of the angel (sung by a high soprano soloist) which is another line that leads into a setting of the Ave Maria (sung by a three-part men’s chorus) which then continues as other lines and layers resume or begin: there will be a mezzo-soprano solo singing a verse of the Magnificat which will overlap with a chant-like setting of another verse of the Magnificat in the women’s voices. These weave in and out of each other in the course of this “Advent” section I've been working on.

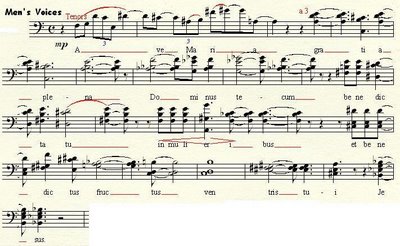

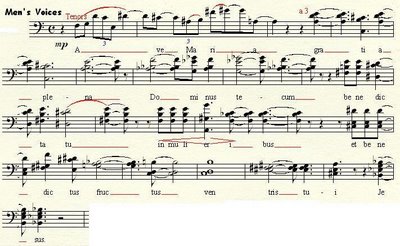

Here, basically, is the “Ave Maria” written out as best I could manage without spending lots of time in this notepad software I’m trying out just for examples on the blog. Here’s the first verse which opens with the chant-like “incipit” sung by tenors:

Here’s the second verse which opens with a comparable “incipit” sung by baritones:

Here’s the second verse which opens with a comparable “incipit” sung by baritones:

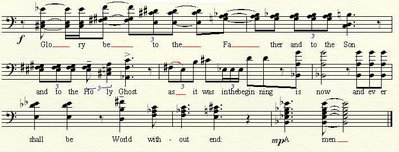

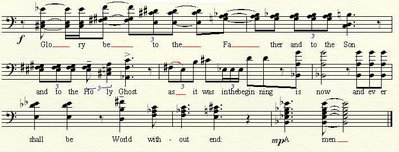

Though it’s not part of the Ave Maria text, I close the section with the men singing the Doxology, which essentially becomes the second half of Verse 2:

Though it’s not part of the Ave Maria text, I close the section with the men singing the Doxology, which essentially becomes the second half of Verse 2:

In this sense, it becomes (musically) a two-part form but with slight alterations between the first and second parts, primarily in the final cadence.

In this sense, it becomes (musically) a two-part form but with slight alterations between the first and second parts, primarily in the final cadence.

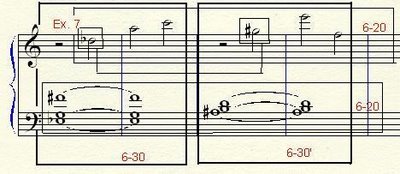

The whole thing uses three hexachords: 6-8 (which is the Angel’s six-note ‘set’ of pitches), 6-20 (which is associated with God or heaven) and 6-30 (with earthly or human associations). The chords are not, basically, standard triads but combinations of pitches that mix major and minor 2nds and more open intervals like 4ths and 5ths (the occasional tritone or augmented 4th), with less prominent major or minor 3rds, differently than one hears them in a standard major or minor triad. So it comes as a surprise to hear – at the end of each part – a progression of standard triads, but not exactly in a standard progression. The first verse cadences from an A Major to an E-flat Major triad. In the Doxology, on the words “Holy Ghost,” what should be A Major to E-flat like the first verse becomes a deceptive resolution from A Major to F Minor (from the set, 6-20), extending the phrase which then ends with a progression of four chords: B Minor to F Minor, A Major now resolving to E-flat Major, each pair of chords a worldly tritone apart and each pair the complement of the other – in all, a progression of four chords consisting of all 12 chromatic notes of the scale.

These three segments are placed to fit into the overall structure of the other layers: together, they make the whole, but the Ave Maria, for example, exists individually as a complete unit in itself. If counterpoint is the juxtaposition of melodic lines against each other to create (vertical) harmony out of their (linear) melodies, I’m doing the same thing here but with complete little pieces.

I had done this, on a more complex scale, thirty years ago when I was teaching at the University of Connecticut and writing a piece for the excellent choir we had there. Called “Whispers of Heavenly Death,” it set two different texts in three different languages and styles: and it was also spaced around the auditorium. On stage were the women’s voices singing a rather English (quasi-Britten) style setting of the Nunc dimittis in English with two soprano soloists who sang lines from Walt Whitman. In the stage-left balcony was a small madrigal choir singing the Nunc dimittis in Latin (but with changing meters and independent of the choir on stage). In the stage-right balcony was the men’s choir singing the Nunc dimittis in Russian in a style more similar to Penderecki in the 1970s: not only was it stylistically independent of the others, it was in a wholly different tempo! Along with this was a brass quintet and a vibraphone: the vibraphone was on stage with the two soloists and the horn on stage with the women’s choir, but the tenor trombone was up with the madrigal choir on the left and the bass trombone with the men on the right. At the very end, the two trumpets came in from the very back of the hall for the benediction.

Not only was it a polyphonic piece with different layers (instead of just lines) moving independently, it was a poly-stylistic and poly-temporal piece that required three conductors. As complex as it sounds, it all fit together very well and sounded great (though I only heard it from my place, conducting the men’s choir in the balcony: I was the only one who could conduct 1/4 note = 45 against the main conductor’s 1/4 note = 60). More amazing, to me, was the fact that on that Thanksgiving morning back in 1976, I had a vague idea of what I wanted to do but not sure how to go about it: by dinner time that evening, the entire piece was complete! So it’s annoying to realize now I’m trying to work out something infinitely simpler but it’s taking several weeks just to get started and who knows how long to complete! (Ah, those were the days, my friend...)

This new piece, however, is nowhere near as complicated as all that: everything works comfortably for one conductor: anything that might sound like it’s a different tempo will be written out in the general one-conductor tempo. And in two weeks, I have about 2 minutes of it done. But at least, it’s a start. Now we’ll see whether I get any more done as Christmas comes and, eventually, goes...

Here, basically, is the “Ave Maria” written out as best I could manage without spending lots of time in this notepad software I’m trying out just for examples on the blog. Here’s the first verse which opens with the chant-like “incipit” sung by tenors:

Here’s the second verse which opens with a comparable “incipit” sung by baritones:

Here’s the second verse which opens with a comparable “incipit” sung by baritones: Though it’s not part of the Ave Maria text, I close the section with the men singing the Doxology, which essentially becomes the second half of Verse 2:

Though it’s not part of the Ave Maria text, I close the section with the men singing the Doxology, which essentially becomes the second half of Verse 2: In this sense, it becomes (musically) a two-part form but with slight alterations between the first and second parts, primarily in the final cadence.

In this sense, it becomes (musically) a two-part form but with slight alterations between the first and second parts, primarily in the final cadence.The whole thing uses three hexachords: 6-8 (which is the Angel’s six-note ‘set’ of pitches), 6-20 (which is associated with God or heaven) and 6-30 (with earthly or human associations). The chords are not, basically, standard triads but combinations of pitches that mix major and minor 2nds and more open intervals like 4ths and 5ths (the occasional tritone or augmented 4th), with less prominent major or minor 3rds, differently than one hears them in a standard major or minor triad. So it comes as a surprise to hear – at the end of each part – a progression of standard triads, but not exactly in a standard progression. The first verse cadences from an A Major to an E-flat Major triad. In the Doxology, on the words “Holy Ghost,” what should be A Major to E-flat like the first verse becomes a deceptive resolution from A Major to F Minor (from the set, 6-20), extending the phrase which then ends with a progression of four chords: B Minor to F Minor, A Major now resolving to E-flat Major, each pair of chords a worldly tritone apart and each pair the complement of the other – in all, a progression of four chords consisting of all 12 chromatic notes of the scale.

These three segments are placed to fit into the overall structure of the other layers: together, they make the whole, but the Ave Maria, for example, exists individually as a complete unit in itself. If counterpoint is the juxtaposition of melodic lines against each other to create (vertical) harmony out of their (linear) melodies, I’m doing the same thing here but with complete little pieces.

I had done this, on a more complex scale, thirty years ago when I was teaching at the University of Connecticut and writing a piece for the excellent choir we had there. Called “Whispers of Heavenly Death,” it set two different texts in three different languages and styles: and it was also spaced around the auditorium. On stage were the women’s voices singing a rather English (quasi-Britten) style setting of the Nunc dimittis in English with two soprano soloists who sang lines from Walt Whitman. In the stage-left balcony was a small madrigal choir singing the Nunc dimittis in Latin (but with changing meters and independent of the choir on stage). In the stage-right balcony was the men’s choir singing the Nunc dimittis in Russian in a style more similar to Penderecki in the 1970s: not only was it stylistically independent of the others, it was in a wholly different tempo! Along with this was a brass quintet and a vibraphone: the vibraphone was on stage with the two soloists and the horn on stage with the women’s choir, but the tenor trombone was up with the madrigal choir on the left and the bass trombone with the men on the right. At the very end, the two trumpets came in from the very back of the hall for the benediction.

Not only was it a polyphonic piece with different layers (instead of just lines) moving independently, it was a poly-stylistic and poly-temporal piece that required three conductors. As complex as it sounds, it all fit together very well and sounded great (though I only heard it from my place, conducting the men’s choir in the balcony: I was the only one who could conduct 1/4 note = 45 against the main conductor’s 1/4 note = 60). More amazing, to me, was the fact that on that Thanksgiving morning back in 1976, I had a vague idea of what I wanted to do but not sure how to go about it: by dinner time that evening, the entire piece was complete! So it’s annoying to realize now I’m trying to work out something infinitely simpler but it’s taking several weeks just to get started and who knows how long to complete! (Ah, those were the days, my friend...)

This new piece, however, is nowhere near as complicated as all that: everything works comfortably for one conductor: anything that might sound like it’s a different tempo will be written out in the general one-conductor tempo. And in two weeks, I have about 2 minutes of it done. But at least, it’s a start. Now we’ll see whether I get any more done as Christmas comes and, eventually, goes...

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

A Christmas Project Part 2

As the saying goes, “what a difference a day makes,” no to mention taking the age-old advice about sleeping on it. Most writers and probably a good many composers will tell you the benefit of “sleeping on a problem.” Somehow, the subconscious works things out in your sleep so when you awake the next morning, suddenly there’s the solution that had been so elusive the night before.

Of course, it also helped to feel brighter and refreshed the next morning, too (despite the fact I was up till 3am blogging), even though I still would not consider myself a morning person. Over the years, I find I am less able to do creative work at night – even blogging goes more smoothly in the morning, something I dislike because it takes away so much of what little creative time there is in my schedule. Working second shift at the station, I often find programming and research there can go much better after I’m off the air, but that uses, I guess, a different part of the brain, though in a way it’s creative, too, just in a different way.

Anyway, on Saturday morning, things in general just looked better: not to so much what I’d written and scribbled over and crossed out the night before, but that I now saw things that I could do and – wait, that looks kind of interesting, so if I... YES! That note, that’s the one – it works! I must have filled three pages with attempts at finding that note – and all I did, really, was take one note in this chord and exchange it for one note in that chord: not only did it sound better, the harmonies it created worked much better (or rather, worked period!) theoretically as well as just sounded better.

(My apologies for all the technical mumble-jumble that follows: I know it’s about as exciting as reading computer programming texts for non-Geeks or all those blah-blah EULAs or whatever they’re called – you know, the on-line agreements for your downloaded free software that you never scroll all the way down to find out that the third Tuesday of every month is your day to go clean out Bill Gates’ cat-litter boxes, right? But bear with me: if it’s not your thing and your eyes are already rolling, check in later for another post.)

What I’d started with was this, the opening chords from the 2003 sketch:

It doesn’t really do anything and doesn’t present a lot of potential. It may have been one reason why I suddenly stopped working on it a couple of weeks later: it wasn’t going anywhere and I didn’t feel like I wanted to take the time to sort it out. At the time, I was working on the Symphony and what I was looking for was some seasonal relaxation, not another major complication!

It doesn’t really do anything and doesn’t present a lot of potential. It may have been one reason why I suddenly stopped working on it a couple of weeks later: it wasn’t going anywhere and I didn’t feel like I wanted to take the time to sort it out. At the time, I was working on the Symphony and what I was looking for was some seasonal relaxation, not another major complication!

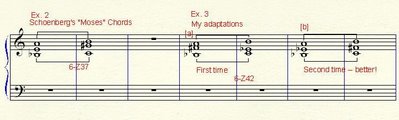

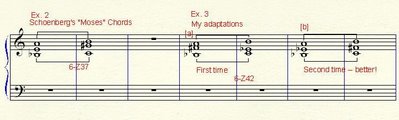

Thinking back to the magical sound that opens one of my favorite works (and one that I first discovered in high school), I decided to get out my score of Arnold Schoenberg’s “Moses und Aron” (yes, after going into New York City to see two different productions at the Met and at City Opera, I broke down and bought the full score, convinced that $100, these days, really was a bargain for such a masterpiece...) and check out the first two chords which represent the “Voice of God” calling out of the Burning Bush.

They’re just two parallel major 7ths a whole step apart: it’s the middle note that defines them, gives them their “color.”

They’re just two parallel major 7ths a whole step apart: it’s the middle note that defines them, gives them their “color.”

I didn’t want to use the same ones (and wanted them to start on different pitches, anyway), just use them as a kind of reference point and a kind of ‘hommage’ – my first attempt (see ex.3a above) made a subtle alteration: the first of the two Schoenberg chords consists of 4ths – well, officially a Perfect 5th which is the inversion of a Perfect 4th and a tritone or augmented 4th (the “Devil in Music” as they always say – at least that’s how they described it centuries ago) – and the second one is built on 3rds, basically: a minor 3rd below the top note, but also a minor 6th (the inversion of a Major 3rd) above the lower note. My first chords are just based on 3rds – a 3rd below the top note and then, symmetrically, a 3rd above the bottom note for the second chord. Eh... However, if I just switch those two inner notes, I get two very different sonorities, going back to the first of Schoenberg’s chords: this time, they’re both based on Perfect 4ths and Tritones, and have a more open and, I thought, more interesting sonority for what I was looking for.

That was when things started to roll.

Anyway, I’m writing a Christmas Piece, okay? This is supposed to be, I guess, the Voice of God sending the Angel Gabriel to Nazareth to tell Mary the Good News. So how can I have intervals like “The Devil in Music” in God’s Chords? Hmmmm...

Now, it’s curious, but composers have often dealt with symbolism in their selections of chords and pitches and keys – I mentioned in the last post the idea of using E-flat and A Major chords because of the three flats or sharps in their respective key signatures representing The Trinity and I have to admit that’s really simplistic: I mean, shouldn’t all religious pieces then be in either E-flat or A Major? Regardless, I thought I should use something a little less dependent on the tritone, at least for these particular chords.

I also wanted to find some kind of “contrapuntal” symmetry beyond just two chords sitting there on a piece of paper. It’s amazing, when you think about it, how those two chords from the Burning Bush actually ignited Schoenberg's whole opera, just from those six notes – well, okay, not a whole opera, since he never figured out how to end the opera: he stopped working at it after the end of the 2nd Act, but that’s another issue.

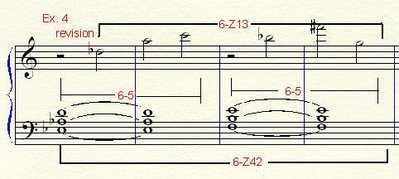

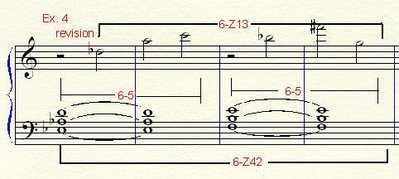

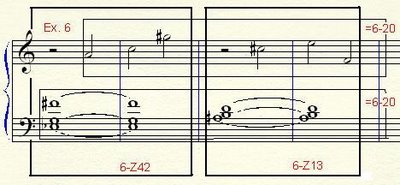

So I have two chords (now transposed to begin on E-flat in the bass) – six pitches, which is a hexachord of a particular number of notes and intervals. Allen Forte labels this one 6-Z42. Its complement – the other six pitches – will either be the inversion of the first six or some other form from a closely-related hexachord (represented in Forte’s language as a Z-related pair), in this case, 6-Z13. By arranging these six notes into two pairs of three – two sub-motives or linear cells – I got an arpeggiated chord similar to the harmony: instead of perfect 4ths & tritones, it’s a major 7th with a minor third below the top note and a major 7th with a minor third above the lower note: now I have both sonorities from Schoenberg’s Burning Bush. Curiously, I found that the linear aspect of each set produced 6-Z13/42 but looking harmonically at it, the first 3 notes of the upper line and the first chord produced a different set: 6-5. Because they’re symmetrical, the second 3 notes and its chord is the first one’s complement.

Now, one set of six notes and some other set of six notes could be related by the number of pitches or the number of intervals they have in common – or perhaps, don’t have in common. In this case, the relationship between 6-5 and 6-Z13/42 is kind of weak. I wanted to find something stronger. Or more outstanding.

Now, one set of six notes and some other set of six notes could be related by the number of pitches or the number of intervals they have in common – or perhaps, don’t have in common. In this case, the relationship between 6-5 and 6-Z13/42 is kind of weak. I wanted to find something stronger. Or more outstanding.

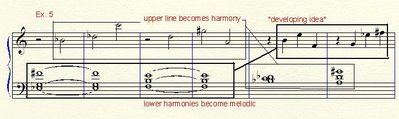

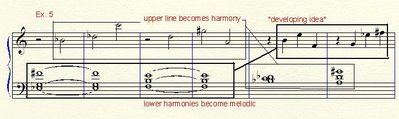

A few transfigurations later and I’ve changed the opening chords a little and found different notes for the upper line. But now it started evolving into other possibilities: Schoenberg used to call his style a “continuous variation” where everything grows organically out of a set of notes, one way or another. In this next example, I found I could take the six notes of the harmony (lower line) and stretch them out linearly in the 2nd half of the example (ignore the rhythms, it was only for spacing), and then also take the first half’s upper line and bunch them together in three-note chords. They look pretty different from each other but they’re really “the same.” This is one way a composer can get variety and yet still maintain “unity.” On a less artistic level, we might just call it “getting more mileage.”

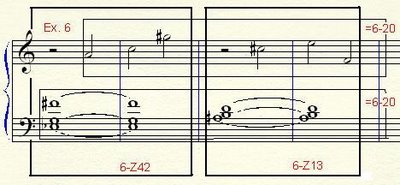

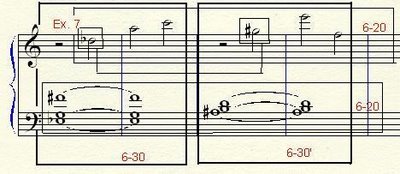

Now, another transformation (see below) shows this contrapuntal harmony/linear thing: while the vertical analysis of the 12 pitches is still a form of 6-Z13/42, the linear analysis – the upper line and then the lower line – create a new set, 6-20.

Now, another transformation (see below) shows this contrapuntal harmony/linear thing: while the vertical analysis of the 12 pitches is still a form of 6-Z13/42, the linear analysis – the upper line and then the lower line – create a new set, 6-20.

This is a very curious set. First of all, most of these groupings of pitches can be transposed to start on any note of the chromatic scale, each of which can, usually, be inverted to create a slightly different collection. But here, there are only four such transpositions possible with 6-20 before it starts duplicating itself. This sense of limitation intrigued me: more intriguing was the fact it’s almost entirely made up of major and minor thirds and minor (but not major) seconds – and no tritones! It is a set that is also known as “Genus tertium” which basically means “Third Race” but which I was looking at (since it seems to do this on its own) as a “generator of thirds,” which is basically what I liked about it: the symbolism of the Trinity and the fact it had no “devil in the music.”

But the relation between 6-Z13/42 and 6-20 was even weaker than it was with 6-5. Could I find something better? Then I arbitrarily took one pitch in one segment and interchanged it with one pitch in the other segment and got this:

But the relation between 6-Z13/42 and 6-20 was even weaker than it was with 6-5. Could I find something better? Then I arbitrarily took one pitch in one segment and interchanged it with one pitch in the other segment and got this:

...which doesn’t seem vastly different. But it creates not only a different vertical sonority, it creates a set with a much more striking relationship with the linear sonority, 6-20. Now, 6-30, the new set, is one that’s closely related to 6-Z13/42, but what I found so interesting was that there is an almost minimal amount of pitches and intervals in common between these two sets. It struck me as odd, in my naive way of looking at things, to think that two sets that are hardly related at all could actually coexist in the same musical passage.

...which doesn’t seem vastly different. But it creates not only a different vertical sonority, it creates a set with a much more striking relationship with the linear sonority, 6-20. Now, 6-30, the new set, is one that’s closely related to 6-Z13/42, but what I found so interesting was that there is an almost minimal amount of pitches and intervals in common between these two sets. It struck me as odd, in my naive way of looking at things, to think that two sets that are hardly related at all could actually coexist in the same musical passage.

But this was what got me going: 6-20 was one principal set with its own intervalic sonorities, and 6-30 was another one which, if you look carefully, consists of three tritones! The D-flat in the upper voice & the G in the first chord; the A & the E-flat in the bass; the C and the F-sharp. So now I had a new symbolism to go by: 6-20 was my spiritual realm (if not specifically God’s Voice) and 6-30 was my earthly realm (if only to have God’s Word [or Music] made flesh).

And from there, I was scribbling away.

Now granted, after an 8-hour day on Saturday and a nearly 10-hour day composing on Sunday – including a successful late-night shift for two hours before midnight – and a less successful but still productive day on Monday, you’d think I’d have more than about 28 measures done by the time I had to go back to work at the end of my vacation Tuesday afternoon. But I prefer to judge it on the quality of that productivity rather than its quantity and the realization that, whether a listener could hear some of these relationships or not (it’s arguable that most listeners today are aware of the fairly obvious ones in traditional tonal music whether they’re listening to Beethoven or the Beatles), this makes it inherently a stronger (if not a better) piece, one that sounds better to me and one that makes more theoretic or logical sense, as well.

If nothing else, the past few days have been exciting just to realize how quickly I was able to get myself, somehow, over the hump that was so depressing on Thursday night when I was almost ready to chuck the whole piece (again). But a little more perspiration helped ignite a little bit of inspiration and I’m pretty happy with what I’ve done so far, 28 measures (just shy of 2 minutes) all coming out of those first six notes.

And just in time: I wanted to use this week’s vacation to get a good strong start on this new piece, whether I finish it in six weeks or six months. I needed to get this much down now because, as I mentioned before, the upstairs apartment has been empty for almost a month. Who knows who the new neighbors will be, if their schedule will work with mine so I can compose uninterrupted or without being self-conscious of disturbing them (what a treat to think “It’s midnight, but I can go compose at the piano now because there’s no one upstairs to worry about waking up!”). The “For Rent” sign came down today: I have no idea who it will be or when they’ll move in, but at least I got a good week’s worth of work in beforehand.

And tomorrow is another day: at least I can still work in the mornings, for a while longer.

Of course, it also helped to feel brighter and refreshed the next morning, too (despite the fact I was up till 3am blogging), even though I still would not consider myself a morning person. Over the years, I find I am less able to do creative work at night – even blogging goes more smoothly in the morning, something I dislike because it takes away so much of what little creative time there is in my schedule. Working second shift at the station, I often find programming and research there can go much better after I’m off the air, but that uses, I guess, a different part of the brain, though in a way it’s creative, too, just in a different way.

Anyway, on Saturday morning, things in general just looked better: not to so much what I’d written and scribbled over and crossed out the night before, but that I now saw things that I could do and – wait, that looks kind of interesting, so if I... YES! That note, that’s the one – it works! I must have filled three pages with attempts at finding that note – and all I did, really, was take one note in this chord and exchange it for one note in that chord: not only did it sound better, the harmonies it created worked much better (or rather, worked period!) theoretically as well as just sounded better.

(My apologies for all the technical mumble-jumble that follows: I know it’s about as exciting as reading computer programming texts for non-Geeks or all those blah-blah EULAs or whatever they’re called – you know, the on-line agreements for your downloaded free software that you never scroll all the way down to find out that the third Tuesday of every month is your day to go clean out Bill Gates’ cat-litter boxes, right? But bear with me: if it’s not your thing and your eyes are already rolling, check in later for another post.)

What I’d started with was this, the opening chords from the 2003 sketch:

It doesn’t really do anything and doesn’t present a lot of potential. It may have been one reason why I suddenly stopped working on it a couple of weeks later: it wasn’t going anywhere and I didn’t feel like I wanted to take the time to sort it out. At the time, I was working on the Symphony and what I was looking for was some seasonal relaxation, not another major complication!

It doesn’t really do anything and doesn’t present a lot of potential. It may have been one reason why I suddenly stopped working on it a couple of weeks later: it wasn’t going anywhere and I didn’t feel like I wanted to take the time to sort it out. At the time, I was working on the Symphony and what I was looking for was some seasonal relaxation, not another major complication!Thinking back to the magical sound that opens one of my favorite works (and one that I first discovered in high school), I decided to get out my score of Arnold Schoenberg’s “Moses und Aron” (yes, after going into New York City to see two different productions at the Met and at City Opera, I broke down and bought the full score, convinced that $100, these days, really was a bargain for such a masterpiece...) and check out the first two chords which represent the “Voice of God” calling out of the Burning Bush.

They’re just two parallel major 7ths a whole step apart: it’s the middle note that defines them, gives them their “color.”

They’re just two parallel major 7ths a whole step apart: it’s the middle note that defines them, gives them their “color.”I didn’t want to use the same ones (and wanted them to start on different pitches, anyway), just use them as a kind of reference point and a kind of ‘hommage’ – my first attempt (see ex.3a above) made a subtle alteration: the first of the two Schoenberg chords consists of 4ths – well, officially a Perfect 5th which is the inversion of a Perfect 4th and a tritone or augmented 4th (the “Devil in Music” as they always say – at least that’s how they described it centuries ago) – and the second one is built on 3rds, basically: a minor 3rd below the top note, but also a minor 6th (the inversion of a Major 3rd) above the lower note. My first chords are just based on 3rds – a 3rd below the top note and then, symmetrically, a 3rd above the bottom note for the second chord. Eh... However, if I just switch those two inner notes, I get two very different sonorities, going back to the first of Schoenberg’s chords: this time, they’re both based on Perfect 4ths and Tritones, and have a more open and, I thought, more interesting sonority for what I was looking for.

That was when things started to roll.

Anyway, I’m writing a Christmas Piece, okay? This is supposed to be, I guess, the Voice of God sending the Angel Gabriel to Nazareth to tell Mary the Good News. So how can I have intervals like “The Devil in Music” in God’s Chords? Hmmmm...

Now, it’s curious, but composers have often dealt with symbolism in their selections of chords and pitches and keys – I mentioned in the last post the idea of using E-flat and A Major chords because of the three flats or sharps in their respective key signatures representing The Trinity and I have to admit that’s really simplistic: I mean, shouldn’t all religious pieces then be in either E-flat or A Major? Regardless, I thought I should use something a little less dependent on the tritone, at least for these particular chords.

I also wanted to find some kind of “contrapuntal” symmetry beyond just two chords sitting there on a piece of paper. It’s amazing, when you think about it, how those two chords from the Burning Bush actually ignited Schoenberg's whole opera, just from those six notes – well, okay, not a whole opera, since he never figured out how to end the opera: he stopped working at it after the end of the 2nd Act, but that’s another issue.

So I have two chords (now transposed to begin on E-flat in the bass) – six pitches, which is a hexachord of a particular number of notes and intervals. Allen Forte labels this one 6-Z42. Its complement – the other six pitches – will either be the inversion of the first six or some other form from a closely-related hexachord (represented in Forte’s language as a Z-related pair), in this case, 6-Z13. By arranging these six notes into two pairs of three – two sub-motives or linear cells – I got an arpeggiated chord similar to the harmony: instead of perfect 4ths & tritones, it’s a major 7th with a minor third below the top note and a major 7th with a minor third above the lower note: now I have both sonorities from Schoenberg’s Burning Bush. Curiously, I found that the linear aspect of each set produced 6-Z13/42 but looking harmonically at it, the first 3 notes of the upper line and the first chord produced a different set: 6-5. Because they’re symmetrical, the second 3 notes and its chord is the first one’s complement.

Now, one set of six notes and some other set of six notes could be related by the number of pitches or the number of intervals they have in common – or perhaps, don’t have in common. In this case, the relationship between 6-5 and 6-Z13/42 is kind of weak. I wanted to find something stronger. Or more outstanding.

Now, one set of six notes and some other set of six notes could be related by the number of pitches or the number of intervals they have in common – or perhaps, don’t have in common. In this case, the relationship between 6-5 and 6-Z13/42 is kind of weak. I wanted to find something stronger. Or more outstanding.A few transfigurations later and I’ve changed the opening chords a little and found different notes for the upper line. But now it started evolving into other possibilities: Schoenberg used to call his style a “continuous variation” where everything grows organically out of a set of notes, one way or another. In this next example, I found I could take the six notes of the harmony (lower line) and stretch them out linearly in the 2nd half of the example (ignore the rhythms, it was only for spacing), and then also take the first half’s upper line and bunch them together in three-note chords. They look pretty different from each other but they’re really “the same.” This is one way a composer can get variety and yet still maintain “unity.” On a less artistic level, we might just call it “getting more mileage.”

Now, another transformation (see below) shows this contrapuntal harmony/linear thing: while the vertical analysis of the 12 pitches is still a form of 6-Z13/42, the linear analysis – the upper line and then the lower line – create a new set, 6-20.

Now, another transformation (see below) shows this contrapuntal harmony/linear thing: while the vertical analysis of the 12 pitches is still a form of 6-Z13/42, the linear analysis – the upper line and then the lower line – create a new set, 6-20.This is a very curious set. First of all, most of these groupings of pitches can be transposed to start on any note of the chromatic scale, each of which can, usually, be inverted to create a slightly different collection. But here, there are only four such transpositions possible with 6-20 before it starts duplicating itself. This sense of limitation intrigued me: more intriguing was the fact it’s almost entirely made up of major and minor thirds and minor (but not major) seconds – and no tritones! It is a set that is also known as “Genus tertium” which basically means “Third Race” but which I was looking at (since it seems to do this on its own) as a “generator of thirds,” which is basically what I liked about it: the symbolism of the Trinity and the fact it had no “devil in the music.”

But the relation between 6-Z13/42 and 6-20 was even weaker than it was with 6-5. Could I find something better? Then I arbitrarily took one pitch in one segment and interchanged it with one pitch in the other segment and got this:

But the relation between 6-Z13/42 and 6-20 was even weaker than it was with 6-5. Could I find something better? Then I arbitrarily took one pitch in one segment and interchanged it with one pitch in the other segment and got this: ...which doesn’t seem vastly different. But it creates not only a different vertical sonority, it creates a set with a much more striking relationship with the linear sonority, 6-20. Now, 6-30, the new set, is one that’s closely related to 6-Z13/42, but what I found so interesting was that there is an almost minimal amount of pitches and intervals in common between these two sets. It struck me as odd, in my naive way of looking at things, to think that two sets that are hardly related at all could actually coexist in the same musical passage.

...which doesn’t seem vastly different. But it creates not only a different vertical sonority, it creates a set with a much more striking relationship with the linear sonority, 6-20. Now, 6-30, the new set, is one that’s closely related to 6-Z13/42, but what I found so interesting was that there is an almost minimal amount of pitches and intervals in common between these two sets. It struck me as odd, in my naive way of looking at things, to think that two sets that are hardly related at all could actually coexist in the same musical passage.But this was what got me going: 6-20 was one principal set with its own intervalic sonorities, and 6-30 was another one which, if you look carefully, consists of three tritones! The D-flat in the upper voice & the G in the first chord; the A & the E-flat in the bass; the C and the F-sharp. So now I had a new symbolism to go by: 6-20 was my spiritual realm (if not specifically God’s Voice) and 6-30 was my earthly realm (if only to have God’s Word [or Music] made flesh).

And from there, I was scribbling away.

Now granted, after an 8-hour day on Saturday and a nearly 10-hour day composing on Sunday – including a successful late-night shift for two hours before midnight – and a less successful but still productive day on Monday, you’d think I’d have more than about 28 measures done by the time I had to go back to work at the end of my vacation Tuesday afternoon. But I prefer to judge it on the quality of that productivity rather than its quantity and the realization that, whether a listener could hear some of these relationships or not (it’s arguable that most listeners today are aware of the fairly obvious ones in traditional tonal music whether they’re listening to Beethoven or the Beatles), this makes it inherently a stronger (if not a better) piece, one that sounds better to me and one that makes more theoretic or logical sense, as well.

If nothing else, the past few days have been exciting just to realize how quickly I was able to get myself, somehow, over the hump that was so depressing on Thursday night when I was almost ready to chuck the whole piece (again). But a little more perspiration helped ignite a little bit of inspiration and I’m pretty happy with what I’ve done so far, 28 measures (just shy of 2 minutes) all coming out of those first six notes.

And just in time: I wanted to use this week’s vacation to get a good strong start on this new piece, whether I finish it in six weeks or six months. I needed to get this much down now because, as I mentioned before, the upstairs apartment has been empty for almost a month. Who knows who the new neighbors will be, if their schedule will work with mine so I can compose uninterrupted or without being self-conscious of disturbing them (what a treat to think “It’s midnight, but I can go compose at the piano now because there’s no one upstairs to worry about waking up!”). The “For Rent” sign came down today: I have no idea who it will be or when they’ll move in, but at least I got a good week’s worth of work in beforehand.

And tomorrow is another day: at least I can still work in the mornings, for a while longer.

Friday, December 08, 2006

A Christmas Project

Three years ago, something inspired me at Christmas time to begin writing a Christmas piece. I usually don’t get “into” the Christmas Holiday Spirit until Christmas Day itself, if I’m lucky, given the incessant barrage of commercialism that is commonly mistaken for Christmas these days (when someone says “don’t you wish Christmas could last all year long,” I look at them and say in my best curmudgeonly graveltones, having seen Christmas ornaments for sale in mid-September and hearing Christmas carols in the stores in mid-November, “don’t you think it does already?”). In past lives, after spending the 4th of July weekend orchestrating Christmas carols for symphony concerts and then programming WITF’s Christmas music by mid-October when the listings still appeared in the magazine – different times, now, different deadlines – I was pretty much sick of Christmas by the time Black Friday even showed up on the horizon. I still get out my Bah Humbug scarf, but this year I was wearing it a week earlier since, for all intents and purposes, the shopping season that is the equivalent of Lent had likewise begun earlier.

So last week, sorting through some papers piled up on the piano, I found the sketches I had begun that Christmas Day of 2003 and wondered what possessed me to do this and then, just as quickly, abandon it. This was not, like “The Christmas Carillon” of the mid-80s, a collection of familiar carols I’d arranged: it was my own version of what would become “The Christmas Story.” Having just seen the Waverly Consort’s medieval version of “The Christmas Story” again (at Gretna Music’s Leffler Chapel performance on Dec. 2nd), it occurred to me I should come back to this and see what I can make of it. I have been wanting to get back to writing something vocal or choral again after several years of purely instrumental and largely abstract music – the scene from Aeschylus’ The Persians not likely to materialize – and certainly, ‘tis the season. Plus, I needed to take a break from the violin and piano “Blues” piece: it was just getting to me, after a while. It’s done, mostly, but I’ll get back to it in January.

Another reason, not to be taken too lightly: my upstairs neighbors had moved out last month and the apartment is still empty. So before new tenants arrive, I have this rare opportunity for an expanse of quietude that I should take advantage of, getting some serious work done on a new piece. Even though it was inconvenient to take vacation time on short notice, I was able to work out a week off, much of which can be spent composing. I set about reacquainting myself with these three-year-old sketches.

One of the things I liked about them was the different texts and overlapping elements of the story. Given my preference for arch-forms and subdivisions according to the Golden Section, there was not much needed to convince me to consider taking this up again: there are seven sections around the central panel that would basically be a meditation on the Holy Family and the text, possibly, “Hodie Christus natus est (This day Christ is born)” – bounded by the Gloria of the Angels and the visit of the Shepherds on one side, then by the visit of the Three Kings and the scene at Herod’s Court on the other side. The Nativity scene and the Birth of Christ (“O magnum mysterium”) is balanced on the other side of the graph by the Slaying of the Innocents (reworking the same material as the lament on the death of the children, “Vox in Rama”). The opening segment for Advent, covering the Annunciation of the Archangel with its “Ave Maria” and “Magnificat” is balanced by the concluding “Nunc dimittis,” St. Simeon’s prayer when Jesus is presented at the temple (“Lord, lettest thou thy servant depart in peace”). It’s all very neat, reminding me of an icon screen in several panels, self-contained musical images of the story, complete with the narration of an Evangelist (in the old Baroque sense of the term).

If I could map out the structure with its various details, I could then “fill in the notes” at a later time, the way a painter might outline the figures and their placement in the foreground before going back to paint in the details of the background, the features of the faces, the colors of the clothes and so on. With any luck, if I can get the Advent portion done before Christmas, work on the Nativity and the Shepherd and the Holy Family’s panels ON Christmas, sketch out the Kings by Epiphany (first week of January) and then the conclusion (later in the month, perhaps), I might be able to have enough to go on to get the work done before summer, not that it might be ready to perform at Christmas 2007. On the other hand, considering I could just as easily do one segment per year – or every three years, the way it’s been going – I’m only hoping I can get it to jump off the drawing board before another decade has passed...

It’s scored for fairly light forces – so far, at least: I’m thinking primarily in terms of organ, since I’m not inclined to get into a large chorus-and-orchestra piece, here. While the Evangelist appears throughout and would ordinarily be a tenor (I’m wondering about using different voices at different segments), there are two incidental solos in this opening section: a high soprano who would sing the wordless “angel solo” that is counterpoint to the recitative describing the appearance of Gabriel to Mary; and a mezzo who then sings the Magnificat in Part 1 (I’m not sure if these solos will continue with any crucial roles in subsequent sections or not). It is primarily a work for chamber choir and so could be done in a church as part of a concert or a non-liturgical service.

The narration becomes one layer with the voice of the angel (wordless) and then the men’s voices singing a chant-like Ave Maria (the angel’s words), three layers in all. Having mapped out the text’s syllables according to the Golden Section (and not surprisingly discovered that each of the texts I’d chosen so far divide fairly well according to these natural proportions), these were then mapped onto the overall structure of the piece, placing certain points to match the individual texts’ structures and arranging them in such a way the climaxes of the Evangelist’s narration (“Behold, a virgin shall conceive”) and the first verse of the “Ave Maria” coincide on the word “Jesus” in a luminous E-flat major triad. At this point, the Magnificat (in English in the mezzo solo) begins and at the climax of the first verse, the women’s voices begin singing the second verse (in Latin), so the two overlap, each continuing under the narration. At the end of the segment, the men’s voices return with the Doxology, chanted to a progression of four triads that will include all twelve pitches before cadencing on E-flat.

While my basic language may not sound traditionally tonal (I’ve posted about this before), it will, at points, open up into standard major and minor triads, though not used in the traditional tonal ways. My “tonic” and “dominant” keys are tritone-related, so the E-flat Major of the opening is answered by the A Major of the central panel. Just as Bach or Mozart might have worked with musical symbolism, I’ve chosen these two keys for the trinity of flats or sharps in their respective key signatures: coincidentally, the birth of Jesus will occur in pure, unadulterated C Major (without sharps or flats, a kind of virgin key, if you will) like a burst of light; the death of the Holy Innocents will focus around a darker F-sharp minor (three sharps). That, basically, is my tonal scheme, before the final segment’s return to E-flat Major.

Unfortunately, it took longer than I had hoped to do what I thought might be fairly mechanical mapping. It was like each text was suddenly fluid and I could expand or contract them proportionally according to how well they might place on the framework. So many possibilities! It was like writing out the rhythms and textures of the piece before even thinking about a specific pitch, finding out how much space between this text and that text, or where this overlap should begin and what the organ might be doing here or there (thinking in terms of “gestures”).

This was finished on the third day of my vacation which has, unfortunately, turned into a kind of half-sick/half-working holiday as I try to rest my back after Thanksgiving’s move and try to get rid of the headaches that have been bothering me for the past week. It has been difficult to concentrate, even though I was only working a few hours in the morning and then a few hours again in the evening. Today, finally getting down to the last basic preparatory phase – what collection of pitches will be the basic source-set for the notes that go onto this framework? – nothing satisfactory was coming up and everything else started acting up until I found myself annoyed by, for instance, the ticking of a clock in another room, the refrigerator running out in the kitchen, the neighbor Doberman barking incessantly (honestly, he’ll bark almost constantly for 20 minutes and then take 10 minutes off, just like a union break, off and on for most of the day) and the rushing sound that is probably only the blood flowing through my head.

Looking at the notes I’d written three years ago to open the piece, they didn’t seem (pardon the pun) pregnant enough, lacking developable ideas and not creating the relationships between pitch-sets I would like to have, now. Ironically, what I had was similar to the opening chords of Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, one of my favorite works, that magical sonority that begins the opera with the Voice of God out of the Burning Bush. By reworking my two chords, prefacing the arrival of the Archangel, I managed something closer to Schoenberg’s sonority, more by way of homage rather than plagiarism. This may have created a greater pressure than I needed because everything from here on out couldn’t measure up to the homage. Finally, I had to put the pen down and go do something else. Tomorrow is another day.

So last week, sorting through some papers piled up on the piano, I found the sketches I had begun that Christmas Day of 2003 and wondered what possessed me to do this and then, just as quickly, abandon it. This was not, like “The Christmas Carillon” of the mid-80s, a collection of familiar carols I’d arranged: it was my own version of what would become “The Christmas Story.” Having just seen the Waverly Consort’s medieval version of “The Christmas Story” again (at Gretna Music’s Leffler Chapel performance on Dec. 2nd), it occurred to me I should come back to this and see what I can make of it. I have been wanting to get back to writing something vocal or choral again after several years of purely instrumental and largely abstract music – the scene from Aeschylus’ The Persians not likely to materialize – and certainly, ‘tis the season. Plus, I needed to take a break from the violin and piano “Blues” piece: it was just getting to me, after a while. It’s done, mostly, but I’ll get back to it in January.

Another reason, not to be taken too lightly: my upstairs neighbors had moved out last month and the apartment is still empty. So before new tenants arrive, I have this rare opportunity for an expanse of quietude that I should take advantage of, getting some serious work done on a new piece. Even though it was inconvenient to take vacation time on short notice, I was able to work out a week off, much of which can be spent composing. I set about reacquainting myself with these three-year-old sketches.

One of the things I liked about them was the different texts and overlapping elements of the story. Given my preference for arch-forms and subdivisions according to the Golden Section, there was not much needed to convince me to consider taking this up again: there are seven sections around the central panel that would basically be a meditation on the Holy Family and the text, possibly, “Hodie Christus natus est (This day Christ is born)” – bounded by the Gloria of the Angels and the visit of the Shepherds on one side, then by the visit of the Three Kings and the scene at Herod’s Court on the other side. The Nativity scene and the Birth of Christ (“O magnum mysterium”) is balanced on the other side of the graph by the Slaying of the Innocents (reworking the same material as the lament on the death of the children, “Vox in Rama”). The opening segment for Advent, covering the Annunciation of the Archangel with its “Ave Maria” and “Magnificat” is balanced by the concluding “Nunc dimittis,” St. Simeon’s prayer when Jesus is presented at the temple (“Lord, lettest thou thy servant depart in peace”). It’s all very neat, reminding me of an icon screen in several panels, self-contained musical images of the story, complete with the narration of an Evangelist (in the old Baroque sense of the term).

If I could map out the structure with its various details, I could then “fill in the notes” at a later time, the way a painter might outline the figures and their placement in the foreground before going back to paint in the details of the background, the features of the faces, the colors of the clothes and so on. With any luck, if I can get the Advent portion done before Christmas, work on the Nativity and the Shepherd and the Holy Family’s panels ON Christmas, sketch out the Kings by Epiphany (first week of January) and then the conclusion (later in the month, perhaps), I might be able to have enough to go on to get the work done before summer, not that it might be ready to perform at Christmas 2007. On the other hand, considering I could just as easily do one segment per year – or every three years, the way it’s been going – I’m only hoping I can get it to jump off the drawing board before another decade has passed...

It’s scored for fairly light forces – so far, at least: I’m thinking primarily in terms of organ, since I’m not inclined to get into a large chorus-and-orchestra piece, here. While the Evangelist appears throughout and would ordinarily be a tenor (I’m wondering about using different voices at different segments), there are two incidental solos in this opening section: a high soprano who would sing the wordless “angel solo” that is counterpoint to the recitative describing the appearance of Gabriel to Mary; and a mezzo who then sings the Magnificat in Part 1 (I’m not sure if these solos will continue with any crucial roles in subsequent sections or not). It is primarily a work for chamber choir and so could be done in a church as part of a concert or a non-liturgical service.

The narration becomes one layer with the voice of the angel (wordless) and then the men’s voices singing a chant-like Ave Maria (the angel’s words), three layers in all. Having mapped out the text’s syllables according to the Golden Section (and not surprisingly discovered that each of the texts I’d chosen so far divide fairly well according to these natural proportions), these were then mapped onto the overall structure of the piece, placing certain points to match the individual texts’ structures and arranging them in such a way the climaxes of the Evangelist’s narration (“Behold, a virgin shall conceive”) and the first verse of the “Ave Maria” coincide on the word “Jesus” in a luminous E-flat major triad. At this point, the Magnificat (in English in the mezzo solo) begins and at the climax of the first verse, the women’s voices begin singing the second verse (in Latin), so the two overlap, each continuing under the narration. At the end of the segment, the men’s voices return with the Doxology, chanted to a progression of four triads that will include all twelve pitches before cadencing on E-flat.

While my basic language may not sound traditionally tonal (I’ve posted about this before), it will, at points, open up into standard major and minor triads, though not used in the traditional tonal ways. My “tonic” and “dominant” keys are tritone-related, so the E-flat Major of the opening is answered by the A Major of the central panel. Just as Bach or Mozart might have worked with musical symbolism, I’ve chosen these two keys for the trinity of flats or sharps in their respective key signatures: coincidentally, the birth of Jesus will occur in pure, unadulterated C Major (without sharps or flats, a kind of virgin key, if you will) like a burst of light; the death of the Holy Innocents will focus around a darker F-sharp minor (three sharps). That, basically, is my tonal scheme, before the final segment’s return to E-flat Major.

Unfortunately, it took longer than I had hoped to do what I thought might be fairly mechanical mapping. It was like each text was suddenly fluid and I could expand or contract them proportionally according to how well they might place on the framework. So many possibilities! It was like writing out the rhythms and textures of the piece before even thinking about a specific pitch, finding out how much space between this text and that text, or where this overlap should begin and what the organ might be doing here or there (thinking in terms of “gestures”).

This was finished on the third day of my vacation which has, unfortunately, turned into a kind of half-sick/half-working holiday as I try to rest my back after Thanksgiving’s move and try to get rid of the headaches that have been bothering me for the past week. It has been difficult to concentrate, even though I was only working a few hours in the morning and then a few hours again in the evening. Today, finally getting down to the last basic preparatory phase – what collection of pitches will be the basic source-set for the notes that go onto this framework? – nothing satisfactory was coming up and everything else started acting up until I found myself annoyed by, for instance, the ticking of a clock in another room, the refrigerator running out in the kitchen, the neighbor Doberman barking incessantly (honestly, he’ll bark almost constantly for 20 minutes and then take 10 minutes off, just like a union break, off and on for most of the day) and the rushing sound that is probably only the blood flowing through my head.

Looking at the notes I’d written three years ago to open the piece, they didn’t seem (pardon the pun) pregnant enough, lacking developable ideas and not creating the relationships between pitch-sets I would like to have, now. Ironically, what I had was similar to the opening chords of Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, one of my favorite works, that magical sonority that begins the opera with the Voice of God out of the Burning Bush. By reworking my two chords, prefacing the arrival of the Archangel, I managed something closer to Schoenberg’s sonority, more by way of homage rather than plagiarism. This may have created a greater pressure than I needed because everything from here on out couldn’t measure up to the homage. Finally, I had to put the pen down and go do something else. Tomorrow is another day.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)